ramonmercado

CyberPunk

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2003

- Messages

- 58,221

- Location

- Eblana

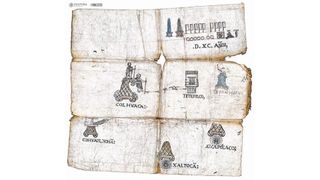

An altar, funeral pot and incense burnes found buried, hidden from the Conquistadors.

Archaeologists in Mexico have uncovered an altar dating back to the 16th Century near Plaza Garibaldi, the square in Mexico City famed for its mariachi musicians.

The altar dates back to the time after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán. Experts say it was located in a courtyard inside a home of an Aztec family, who would have used it to honour their dead.

It contains a pot with human ashes.

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS Image caption, The pot containing human ashes was one of the items found at the altar

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS Image caption, The pot containing human ashes was one of the items found at the altar

The original discovery was made in August but only announced by Mexico's National Institute for Anthropology and History (Inah) on Tuesday, after archaeologists had spent three months studying the site.

The altar dates is thought to date back to the period between 1521, when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés defeated the Aztec ruler of Tenochtitlán, and 1610. The battle of Tenochtitlán is seen as the beginning of the end of the Aztec empire, which in its heyday ruled over the central Mexican highlands.

The archaeologists behind the discovery say that the inhabitants of the house would have held a ritual "to bear witness to the ending of a cycle of their lives and of their civilisation" at the altar.

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS Image caption, Anthropomorphic figures were also among the items uncovered

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS Image caption, Anthropomorphic figures were also among the items uncovered

Archaeologist Mara Becerra says that the altar was found four metres (13ft) below ground, underneath several layers of adobe mud. According to Ms Becerra, the inhabitants of the house wanted to hide it from the prying eyes of the Spanish conquistadors. She believes they were Mexica, the indigenous people who lived in the Valley of Mexico and who founded the Aztec empire. The altar contained a pot with human ashes and 13 intricately decorated incense burners.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-59489046

Archaeologists in Mexico have uncovered an altar dating back to the 16th Century near Plaza Garibaldi, the square in Mexico City famed for its mariachi musicians.

The altar dates back to the time after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán. Experts say it was located in a courtyard inside a home of an Aztec family, who would have used it to honour their dead.

It contains a pot with human ashes.

The original discovery was made in August but only announced by Mexico's National Institute for Anthropology and History (Inah) on Tuesday, after archaeologists had spent three months studying the site.

The altar dates is thought to date back to the period between 1521, when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés defeated the Aztec ruler of Tenochtitlán, and 1610. The battle of Tenochtitlán is seen as the beginning of the end of the Aztec empire, which in its heyday ruled over the central Mexican highlands.

The archaeologists behind the discovery say that the inhabitants of the house would have held a ritual "to bear witness to the ending of a cycle of their lives and of their civilisation" at the altar.

Archaeologist Mara Becerra says that the altar was found four metres (13ft) below ground, underneath several layers of adobe mud. According to Ms Becerra, the inhabitants of the house wanted to hide it from the prying eyes of the Spanish conquistadors. She believes they were Mexica, the indigenous people who lived in the Valley of Mexico and who founded the Aztec empire. The altar contained a pot with human ashes and 13 intricately decorated incense burners.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-59489046