Here is the salvaged / reconstructed article from Fortean Times #141 (December 2000)

AWAY WITH THE FAERIES

Long before crop circles caught the headlines there were fairy rings. GORDON RUTTER explores the legends and lore of this mysterious phenomenon, as well the various explanations which have been offered to account for it.

Fairy rings are, and always have been, a lot more common than today’s more famous crop circles, but originally their origins were as mysterious and ascribed to similar causes. Usually, a fairy ring is visible as a noticeable circle appearing in grass. Some rings are formed by a luxuriant growth, taller and of a darker green than the grass at their centre.

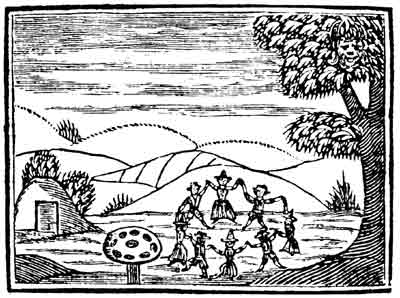

Others seem to be the opposite: a patch of poorly-growing grass or even bare earth in a circular pattern. When both types combine, the luxuriant growth has an area of bare ground as an inner circle. We now know that fairy rings are actually produced by fungi – see panel – but this was not always the case. As the common name for the phenomenon implies, they were widely explained as the result of a gathering of fairies that ended with a circular dance. Such was the energy used in their dancing that the ground was permanently marked.

This gives rise to some of the other common names given to fairy rings, including fairy dances, fairy courts, fairy walks and fairy grounds. In Sussex, fairy rings were called ‘hag tracks’, while in Devonshire it was believed that fairies would catch young horses in the night and ride them round in circles. The dishevelled state of livestock in the morning was often attributed to being ‘hag-ridden’.

The perils of straying into a fairy ring terrified rural folk in 17th century England, as evidenced by an incident recorded by the antiquarian John Aubrey (1626–97). Writing in 1663, he tells us that his curate, Mr Hart, was out walking over the local downs one night when, as he approached a known fairy ring, he was surprised to see “a quantity of pygmies, or very small people, dancing round and round, and singing and making all manner of small odd noises.” Seemingly paralysed, Mr Hart could only stand and observe until, eventually, the little folk observed him. They rushed towards him and surrounded him, causing him to fall over. On the ground, the small creatures swarmed all over him, pinching him and making tiny, rapid humming noises. Eventually, they withdrew and, when day broke, Hart discovered himself in the middle of the fairy ring. He was lucky. Fairylore is full of stories of careless trespassers whisked off to fairyland, returning the following day to find some 20 years have elapsed, or forced to dance in the circular revel until some faithful friend comes to the rescue.

Explanations for fairy rings have been as wild and diverse as the mushrooms that actually cause them. Just as fungi grow in all parts of the world, so fairy rings are a worldwide phenomenon and explanations of them occur in most cultures. An early naturalistic explanation put the blame fairly and squarely on the rear ends of cattle. During the winter, cattle are fed with bails of hay and as they gather around these they form a wheel-like arrangement with their heads in the centre. Cows being cows, the natural occurs and, as they feed, they deposit high-quality manure around the perimeter. This manure, so the theory goes, causes the grass on which it falls to be more luxuriant. Of course, this does not account for many rings observed where no cattle or other animals have grazed, eg in woodland.

Shakespeare was aware of many of the folkloric aspects of fairy rings. For example, in The Tempest (Act V, scene i), Prospero declaims:

“You demi-puppets that By moonshine do the green sour ringlets make, Whereof ewe not bites; and you, whose pastime Is to make midnight mushrooms…”

Rural folk observed that their livestock often found the grass from fairy rings to be unpalatable (Shakespeare’s “green sour ringlets”), while some thought it was actually poisonous. t is amusing to note that one of the earliest explanations for crop circles was originally applied to fairy rings. It was said – perhaps partly in jest – that amorous hedgehogs chase each other round and round in circles until mating ensues, causing the grass to be heavily trampled. This certainly made sense of those rings that looked like circular tracks of bare earth. A subterranean variation, in the 1700s, blamed moles racing round in underground circular tunnels, their fæces promoting the grass growth above. Presumably those rings composed of both luxuriant growth and bare earth were combinations of cattle feeding above while hedgehogs ran rampant below!

The circular movement of other animals was implicated by association: horses and goats tied to a stake; starlings swooping in great circular motions; and ants or snails in majestic circular processions. One 18th-century author recounted how he sat and watched ants marching around in circles for 30 minutes, with each ant completing 20 laps in this manner. Even the slime from snails was blamed as engendering loathsome toadstools by a kind of spontaneous generation. An interesting variation on the bare earth fairy rings comes from the Austrian Tyrol, where it was thought to be earth scorched by a dragon. However, just why a dragon should fly in tight circles is not explained. In Denmark, it used to be thought that elves were made of hot stuff and so the earth was scorched as they danced round in circles.

In The Netherlands, the heat came from Old Nick himself. During the night, the Devil would be abroad collecting milk from cows, storing it in a massive churn which he carried around with him. Even the Devil had to rest, and when he placed the churn, heated by the fires of Hell, on the ground, it left the distinctive circular scorch mark. Explanations from France and Germany invoke witchcraft. Called ‘ronds de sorcières’ and ‘Hexenrings’ respectively, they are caused by sorcerers or witches dancing round in circles (in Germany, specifically on Walpurgis Night). French folklore holds that an enormous toad with bulging eyes squats in the centre of every fairy ring, a thing to be feared by country peasants.

Fairy rings were credited with magical properties beyond the common fairy connection; for example, associations with prophecy, fortune-telling and luck. In the West Country and Scotland, it is said that a maiden can improve her looks by bathing her face in dew collected on a May morning; but if the dew is collected from inside a fairy ring, or if she stands in a fairy ring to collect or apply the dew, then her appearance is turned into that of an old crone, complete with spots and blemishes.

Some farmers regard the presence of a fairy ring on their property as a sign of good luck or as a marker of treasure – treasure which can only be found with the help of witches or fairies. In some regions, stepping into a fairy ring will bring good luck; in others, it will bring misfortune. It’s always wise to check up on local folklore when venturing out, just to be on the safe side.

Aubrey, in his topographical survey of Wiltshire – written 1656-1691 –compared fairy rings to smoke rings and ringworm. Ringworm is caused by a fungal contamination, so he was very close, but he eventually concluded that fairy rings were caused by exhalations from the earth of a ‘fertile subterraneous vapour’. Instead of Paul Deveraux’s ‘earth lights’ we have what might be termed ‘earth farts’.

Despite the true origin of fairy rings becoming known as far back as the 1790s, the phenomenon is still a beautiful and mysterious act of nature. The rings grow slowly, with annual increases of diameter ranging from four to 12 inches (10 to 30 cm). The exact size increase depends upon the species of fungus and the prevailing weather conditions. Large examples of fairy rings can be seen in many relatively undisturbed grassland areas. Some fairy rings in the UK’s Lake District are believed to be in excess of 600 years old. One ring in France – formed by Clitocybe geotropa – is over half a mile (0.8 km) in circumference and it is believed to be over 700 hundred years old. While fairy rings usually appear as changes in the colour and texture of the grass, at certain times of the year the fungi that cause them appear above ground (depending upon still poorly understood factors). Of the 60 or so species that produce fairy rings, the majority are what we would think of as mushrooms or toadstools, but there are other types. Puffballs can produce fairy rings; the giant puffball can grow to a circumference of 6.5 feet (2 m), and a ring made up of these would be as impressive as Stonehenge.

In recent times, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a firm believer in the existence of fairies, could not fully let go of the old beliefs associated with fairy rings. While admitting they were simply a fungal growth, he wrote (in The Coming of the Fairies, 1923): “It might be asserted and could not be denied that the rings once formed, whatever their cause, would offer a very charming course for a circular ring-a-ring dance. Certainly from all time these circles have been associated with the gambols of the little people.”

As a general rule, fairy rings are harmless. In fact some (but not all) of the species that produce them are fine edibles. The worst problem they cause is what some regard as an unsightly blemish on a lawn. Many fungicides are available to combat fairy rings, but with a wide range of causative species not all fairy rings can be destroyed by the same treatment.

Personally, I think a fairy ring is a true wonder of nature and I would be proud to have a fine example of one in my garden. And, if blessed with this fungal manifestation, I’d be sure to keep my dew-collecting female friends away

during the month of May.

FAIRY RING A DING

The fairy ring was definitively identified as a fungal growth pattern in 1792 by William Withering. The example he studied in Shropshire was identified as a species called Marasmius oreades, whose modern common name is the fairy ring mushroom. In reality, this is one of 60 or so different species which produce fairy rings.

There are actually three distinct types of fairy rings, classified according to their effect on grass and surrounding vegetation. The visible effects on grass can be seen all year

round, whereas the mushrooms (the fruitbodies of fungi) can only be seen when the time and conditions are right for producing spores.

The first type of fairy ring is actually ‘invisible’, having no visible effect on surrounding vegetation; they can only be seen when the fruit bodies appear as a circle of mushrooms.

The second type is observed as a vigorous growth of vegetation, often leading to taller and darker grass. With this type, the mushrooms are produced at the outer edge of the ring. The third type of fairy ring shows some sort of damage to the vegetation, usually a bare or damaged patch, with luxuriant growth forming a border between an inner and an outer ring.

All fairy rings are produced in the same manner. Initially a spore (the fungal equivalent of a seed) lands on some suitable ground. This spore then starts to grow underground, pushing out a white mass of mycelium (fungal threads – the actual body of the fungus itself) in all directions. As this increases in size, the central part eventually dies off, leaving a disc of mycelium growing at the outer or leading edge.

Fungi release digestive chemicals (enzymes) into the ground to break down their food, which they then suck up. Unfortunately, they are sloppy eaters and not all of this digested food is taken up. These nutrients then stimulate the surrounding vegetation. As a result of this, the grass grows more luxuriantly at the leading edge where the extra food supply is present. The death of the mycelia at the trailing (inner) edge returns nutrients to the soil, also stimulating a growth of grass.

With some species, the mycelia are very tightly bound together, so tightly, in fact, that water cannot penetrate the ground where they are. Thus the areas of luxuriant growth represent the areas of actively growing and feeding mycelia; the bare patches represent regions where water cannot penetrate and the grass simply dies off. Other reasons for the central bare patches include the presence of toxins manufactured by the fungus; a depletion of nutrients; and poor æration.

Eventually, when season and weather allow, fruit bodies (usually in the form of mushrooms) are produced to release spores and start the cycle again. Sometimes, several years may go by before mushrooms are actually seen at a fairy ring. Fairy rings may not be complete circles, as parts of the circle of mycelium become damaged and die off, leaving a crescent shape. Other formations may include multiple overlapping rings as, in time, parts of the original perimeter become the centres of their own circular expansion.

SALVAGED FROM THE WAYBACK MACHINE:

https://web.archive.org/web/20040720074357/http://www.forteantimes.com/articles/141_faeryrings.shtml

(Some minor formatting changes had to be done in this transcription.)