Floyd

Antediluvian

- Joined

- Apr 2, 2019

- Messages

- 7,893

Southwark: Rare Roman mausoleum unearthed in London

Not sure why hard hats are necessary though.....

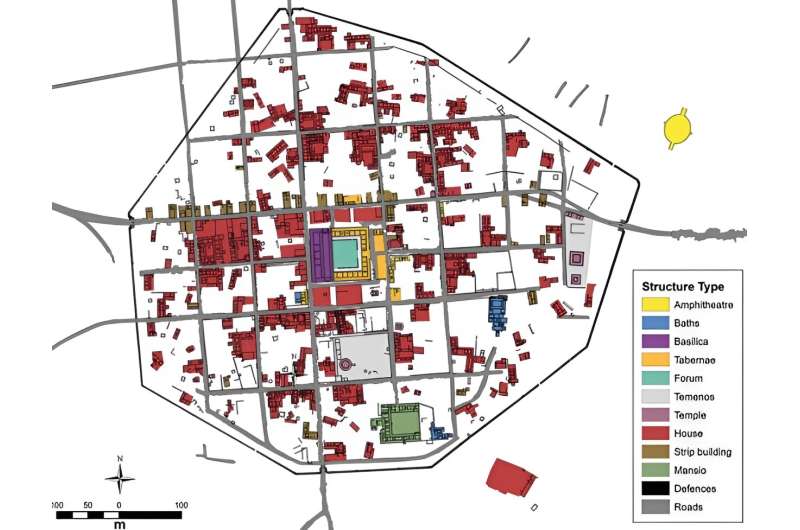

A "completely unique" Roman mausoleum has been discovered by archaeologists in south London.

The remains of the structure at the Liberty of Southwark site in Borough have been described as "extremely rare" and feature preserved floors and walls.

Archaeologists think the site was used as some form of burial ground or tomb for wealthier members of Roman society.

Work on creating a permanent display is planned, says the team behind the find.

The discovery was made at the Liberty of Southwark excavation site

The dig was led by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) on behalf of Landsec and Transport for London (TfL).

MOLA believes the quality of preservation makes it the most intact Roman mausoleum ever to be discovered in Britain.

Alongside the central mosaic, raised platforms were found and steps on the lowest side were still intact.

Excavators were surprised to find two layers to the site, with another similarly designed mosaic found beneath the first floor. They believe that the building was modified at some point, with the floor raised.

"All signs indicate this was a substantial building," says MOLA, "perhaps two storeys high."

A second mosaic was found beneath the first, suggesting the floor was raised at some point

While the site is believed to be a burial location, no coffins were found. However, more than 100 coins, fragments of pottery, roofing tiles and pieces of metal were discovered.

There has been a sustained period of excavation at the site, where the largest Roman mosaic found in London for over 50 years was uncovered in 2022.

Antonietta Lerz, senior archaeologist at MOLA, says the site is a "microcosm for the changing fortunes of Roman London" and provides "a fascinating window" into the life of its settlers.

The aim is to preserve the area alongside continued urban development

Archaeologists from MOLA hope to pinpoint the age of the mausoleum and have provided a three-dimensional model of the site.

Landsec and TfL say they are committed to restoring and retaining the mausoleum for permanent public display.