ramonmercado

CyberPunk

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2003

- Messages

- 58,250

- Location

- Eblana

The stone Age Dutch lived alongside beavers,

For thousands of years, beavers had a big influence on the Dutch ecosystem and the people that lived there. This is the conclusion of research by archaeologist Nathalie Brusgaard. The rodents were used for food, clothing and tools, and created a landscape hospitable to many other species.

Beavers may seem like a recent arrival to the Netherlands, with their growing presence in recent years. The species became extinct there in the 19th century and was reintroduced in 1988. But before that beavers were widespread for thousands of years. "It really is a native species," says Brusgaard. "In our research we wanted to look at how people dealt with the beaver's presence in the past. There was no good picture of that until now."

Together with fellow archaeologist Shumon Hussain (Aarhus University), Brusgaard analyzed previous excavations in the Netherlands, southern Scandinavia, the Baltic region and Russia. These showed that beavers were a much larger part of the human diet and landscape of northern Europe than had previously been thought.

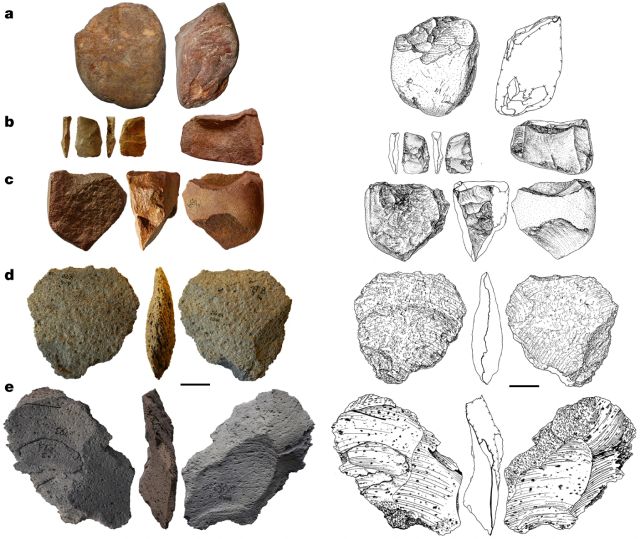

Hunter-gatherers hunted beavers in the Middle and Late Stone Age for their meat, fur and castoreum, and used their bones and teeth to make tools. Beavers were one of the most common mammals at some archaeological sites in the Netherlands according to research recently published in The Holocene.

According to Brusgaard, the beavers created a diverse ecosystem. They change the water level in their habitat so the entrance to their lodge is flooded but they can sleep in the dry. To achieve this, they need the water at a certain level, which they control by building dams.

Other organisms, such as fish, waterfowl and certain plants, benefit from the resulting landscape. "Beavers create a lot of dynamism in a forest, which is good for biodiversity. At archaeological sites where there were many beaver traces, there were also many traces of otters, wild boar, pike, perch and carp. These species thrive in the ecosystem that beavers create."

The research suggests that people liked to live in these "beaver landscapes" because of the presence of food and resources. "We suspect that hunter-gatherers benefited from the rich biodiversity that beavers created."

https://phys.org/news/2023-10-beavers-big-people-stone-age.html

For thousands of years, beavers had a big influence on the Dutch ecosystem and the people that lived there. This is the conclusion of research by archaeologist Nathalie Brusgaard. The rodents were used for food, clothing and tools, and created a landscape hospitable to many other species.

Beavers may seem like a recent arrival to the Netherlands, with their growing presence in recent years. The species became extinct there in the 19th century and was reintroduced in 1988. But before that beavers were widespread for thousands of years. "It really is a native species," says Brusgaard. "In our research we wanted to look at how people dealt with the beaver's presence in the past. There was no good picture of that until now."

Together with fellow archaeologist Shumon Hussain (Aarhus University), Brusgaard analyzed previous excavations in the Netherlands, southern Scandinavia, the Baltic region and Russia. These showed that beavers were a much larger part of the human diet and landscape of northern Europe than had previously been thought.

Hunter-gatherers hunted beavers in the Middle and Late Stone Age for their meat, fur and castoreum, and used their bones and teeth to make tools. Beavers were one of the most common mammals at some archaeological sites in the Netherlands according to research recently published in The Holocene.

According to Brusgaard, the beavers created a diverse ecosystem. They change the water level in their habitat so the entrance to their lodge is flooded but they can sleep in the dry. To achieve this, they need the water at a certain level, which they control by building dams.

Other organisms, such as fish, waterfowl and certain plants, benefit from the resulting landscape. "Beavers create a lot of dynamism in a forest, which is good for biodiversity. At archaeological sites where there were many beaver traces, there were also many traces of otters, wild boar, pike, perch and carp. These species thrive in the ecosystem that beavers create."

The research suggests that people liked to live in these "beaver landscapes" because of the presence of food and resources. "We suspect that hunter-gatherers benefited from the rich biodiversity that beavers created."

https://phys.org/news/2023-10-beavers-big-people-stone-age.html