Early potters.

Pottery making may not have emerged in one Big Bang–like event. Instead, it was more like a cluster of ceramic eruptions among ancient East Asian hunter-gatherer groups as the last Ice Age waned, a new study suggests.

East Asian hunter-gatherer populations living about 700 kilometers apart made and used cooking pots in contrasting ways between around 16,200 and 10,200 years ago, says a team led by Shinya Shoda, an archaeologist currently based at the University of York in England. Each of those groups

probably invented its own distinctive pottery-making techniques, the scientists suspect.

“Our results indicate that there was greater variability in the development and use of early pottery than has been appreciated,” Shoda says.

Pieces of ceramic cooking pots from one group preserved chemical markers of fish, including salmon, Shoda’s group reports in the Feb. 1

Quaternary Science Reviews. Early pottery making by those hunter-gatherers accompanied seasonal harvests of migrating fish, the researchers say

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/food-residues-offer-taste-pottery-diverse-origins-east-asia

New findings on the use of pottery in ancient days.

Broken, charred and still crusted with nearly 8000-year-old food, the remnants of ancient pottery found across northern Eurasia wouldn’t be mistaken for fine china. But the advent of this durable technology—used to cook and store abundant plant and animal resources—was a huge step forward for hunter-gatherers in this part of the globe. It was also home-grown, new research suggests.

For decades, researchers believed pottery arrived in Europe along with agriculture and domesticated animals, as part of a “package” of technologies that spread northward from Anatolia beginning about 9000 years ago. Pots found in Northern Europe dating around the same time were thought to be mere knockoffs by hunter-gatherers copying their more sophisticated farmer neighbors, says Thomas Terberger, an archaeologist at the University of Göttingen who was not involved with the new research. “A generation ago, nobody looked to the East.”

But a study published today in Nature Human Behaviour

tells a different story. Beginning about 20,000 years ago, the know-how needed to make and use pottery spread among groups of hunter-gatherers in the Far East. This containers replaced less durable vessels made of hide and skin, and were better able to withstand fire than wood bowls. Starting about 7900 years ago, clay pots became common from the Ural Mountains to southern Scandinavia within just a few centuries.

SIGN UP FOR OUR DAILY NEWSLETTER

Get more great content like this delivered right to you!

SIGN UP

To map pottery’s spread, Rowan McLaughlin, an archaeologist at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, and colleagues analyzed broken shards collected from 156 sites around the Baltic Sea and across the European part of the former Soviet Union—many stored in museums in modern-day Russia and Ukraine. By sampling burned crusts of food stuck to the broken pots—remnants of bygone meals—they were able to get hundreds of new radiocarbon dates.

Fat residues revealed whether meat from ruminants like deer or cattle was on the menu, or whether people were boiling fish soup, pork, or plants instead. And comparing decorations and pot shapes helped the team map how pottery trends spread from community to community.

Though the raw material to make clay pots was widely available, the technical knowledge needed to shape and fire them must have been passed from person to person. New cooking and food preparation techniques had to be learned as well.

Put together, the data suggest

pottery spread across parts of northern Eurasia rapidly, the team reports. Within a few hundred years, the technology swept north and west from the Caspian Sea, all the way to the eastern shore of the Baltic and southern Scandinavia.

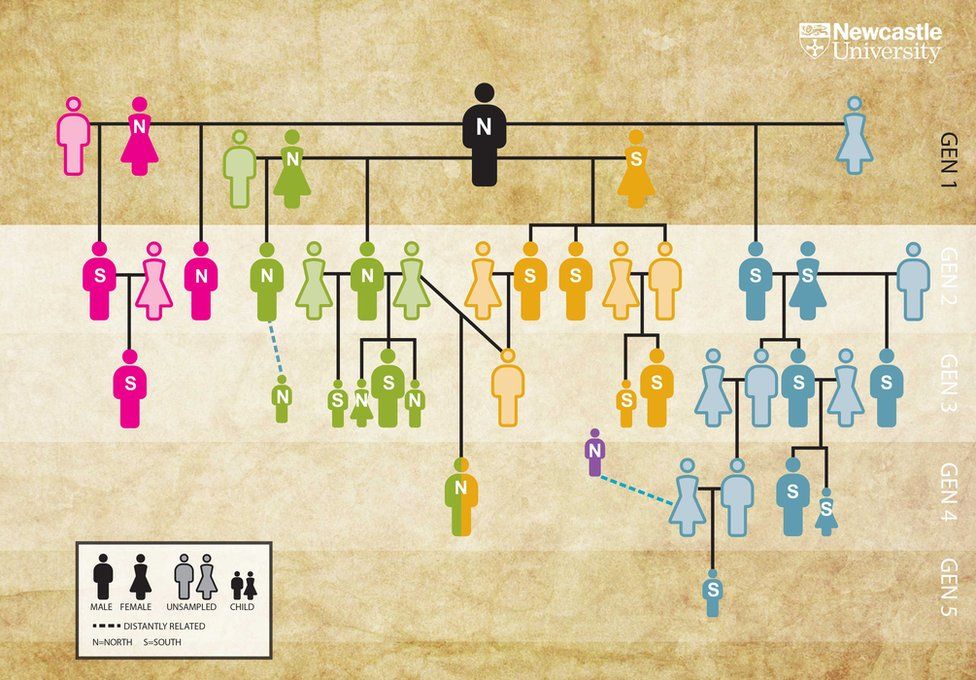

The speed of the spread suggests potterymaking knowledge passed from group to group, rather than being introduced by new people migrating into the region. “There’s no way a population could grow that fast,” McLaughlin says.

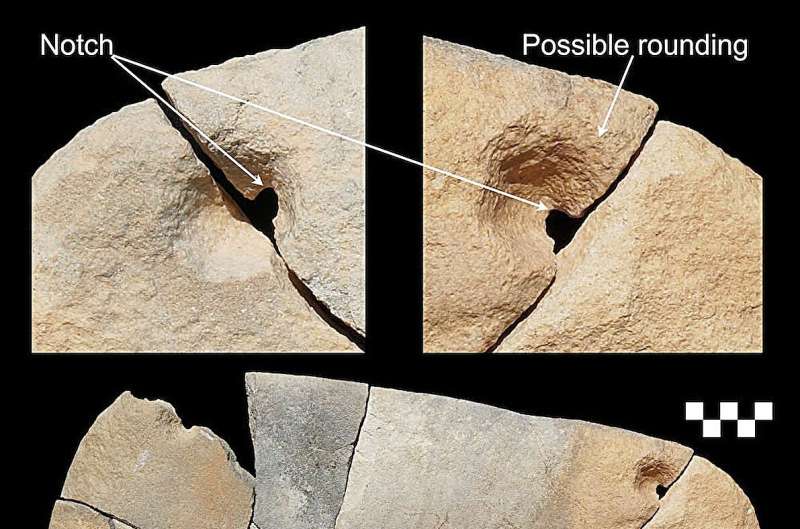

Burned crusts of food on a pot used by early hunter-gatherers in northeastern Europe about 7500 years agoEKATERINA DOLBUNOVA/BRITISH MUSEUM

Lucy Kubiak-Martens, an archaeobotanist at BIAX Consult, a commercial archaeology company in the Netherlands who was not involved with the paper, agrees with that interpretation. “It seems the knowledge traveled, not people,” she says.

If so, that would contrast with how similar technology spread out from Anatolia: Recent genetic evidence suggests that around the same time, farmers from Anatolia

brought their own pottery styles and traditions with them as they expanded into southern Europe.

https://www.science.org/content/article/ancient-hunter-gatherers-were-potters-too