Fabio Picasso

Ephemeral Spectre

- Joined

- Mar 31, 2024

- Messages

- 361

A Civilization Disappeared Deep in the Amambay, Paraguay?

Between 1975 and 1979, a group of Paraguayan military and former military personnel, together with academics from Argentina, ventured deep into the Amambay in search of what, according to the version of a German adventurer, would be the vestiges of a very ancient Viking fortress. This is the story of that unknown series of expeditions and their peculiar leader, the controversial French anthropologist Jacques de Mahieu.

The Viking saga inspired veritable rivers of ink. From Scandinavia to Byzantium, passing through the North Sea, the Mediterranean, the British Isles, Sicily; southern, central, eastern and western Europe and Kievan Rus, among many other locations, that intrepid people of warriors and merchants took to the sea with such determination that they expanded their influence with the help of their fast longships.

But not everything was blood, fire and conquest; also discovery and colonization. The oldest records speak of names that reached the most remote points of the world known until then and to lands never seen before.

Jacques de Mahieu, in the Tacuatí excavations

Thanks to the site of L'Anse aux Meadows, on the island of Newfoundland, (Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador), it is known that the Vikings arrived in America at least 500 years before Christopher Columbus and it is speculated that this would be Vinland (the land described in the fascinating sagas of Eric the Red and that of the Greenlanders).

It is impossible to know if these skilled navigators considered – or could – continue further south of the American continent, explore the coasts and look for a safe place to spend the winter, or perhaps settle, interact and mix with the local population.

In this sense, there are academics who venture to work on this last possibility and outline bold theories. One of these was the controversial Jacques de Mahieu, a staunch defender of the Viking presence in pre-Columbian America.

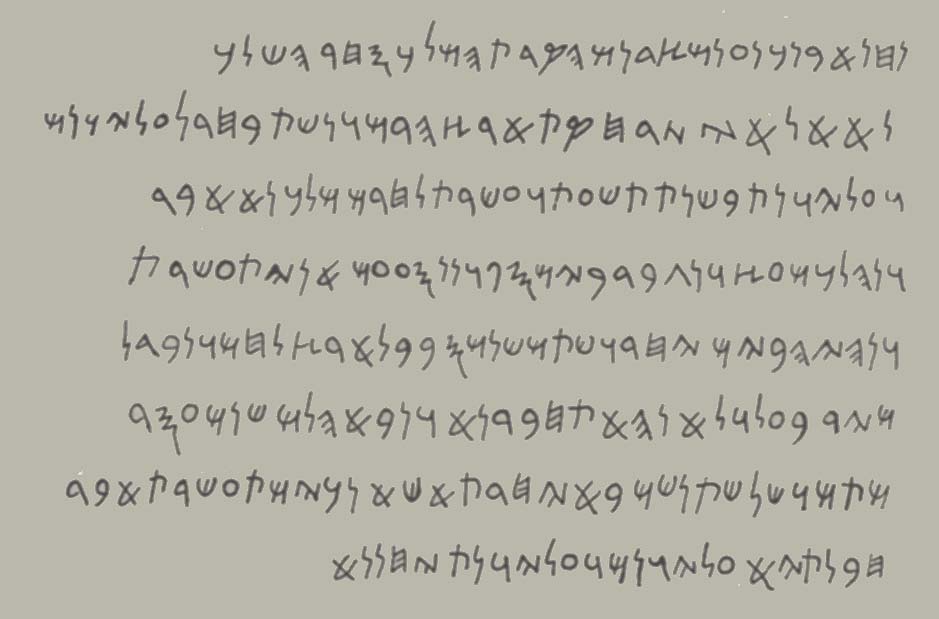

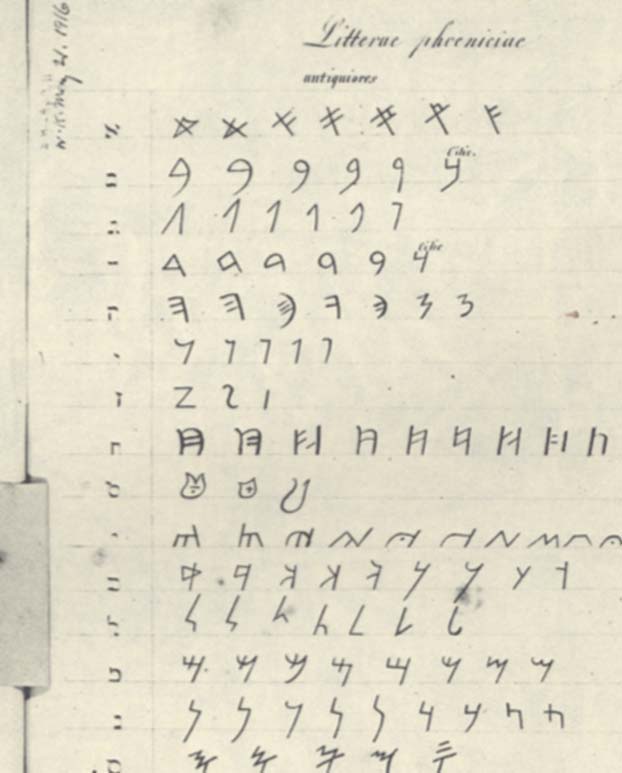

Alleged runic inscriptions found on Guazú Hill

JACQUES DE MAHIEU

Jacques de Mahieu was born at the end of October 1915 in Marseille, France. It is known that during his youth he was involved with extreme right-wing movements and acted as an informant for the Vichy regime. Additionally, he fought against the Soviets in the service of Nazi Germany in the 33rd Charlemagne Volunteer SS Grenadier Division in the Waffen-SS.

As an –alleged– collaborator with the Nazis during the occupation, De Mahieu knew the risks of remaining in France and fled to Argentina shortly after the defeat of the Axis powers in World War II. The Frenchman took root in South American soil. He gained prestige and made a place for himself in the circles of anthropological studies in Buenos Aires, climbing positions until he reached the great university halls, enjoying an important reputation as a graduate in philosophy and a doctor in political sciences and economic sciences.

Our protagonist wrote at least half a dozen books about the alleged Viking adventures from the frozen wastelands of the north of the continent to the current border between Brazil and Paraguay.

To understand De Mahieu and the reasons that encouraged him to risk his life in the hot Paraguayan jungle and confront the entire conventional community of scientists, one must first understand the belief he professed.

De Mahieu mixed aristocratic and nationalist ideas, and focused his anthropological and sociological studies on the importance of race in history and culture. He was influenced by scientific racism and conceived theories “reinforced” with esotericism by embracing what related to the “Aryan race”, the cornerstone of Nazi mythology.

Likewise, he followed the theory of “Nordicism”, which is related to that of the “Aryan race” because the Nazis considered that the “Nordic race” (Vikings and their relatives) was the most superior branch of the “Aryan race” ( Herrenvolk).

Convinced of the great adventures that only members of the “Aryan race” could undertake, he soaked up the ability of the Vikings to reach, explore and conquer distant lands and looked for any evidence in these parts that would serve to highlight the greatness of the Vikings. “Aryans”.

FRITZ BERGER

Little is known about the German engineer Fritz Berger. In his fifties, obese and addicted to whiskey, Berger toured South America without settling anywhere. He was in Asunción during the Chaco War and provided “very good and loyal services” to the Paraguayan Army in command of one of the workshops where weapons captured from the Bolivian Army were reconditioned. After the war, he undertook the search for oil fields in the state of Paraná, Brazil, without much success.

His exploration took him to the border with Paraguay, where he “made discoveries of another nature” such as being “the largest runic complex in the world,” or what he believed were Viking runes.

Berger spent time with the natives, the oldest inhabitants of the area, and became obsessed with the runes when he was seduced by the stories of unimaginable treasures and vestiges of a disappeared, forgotten people, among versions that he collected from his talks with the aboriginal elders. .

“At that time there reigned in the region a powerful and wise king named Ipir. He was white and had a long blonde beard. With men of his race and with native warriors who were loyal to him, they lived in a large village located on the top of a hill. He had fearsome weapons and great wealth in gold and silver. One day, however, he was attacked by wild tribes and disappeared forever. This is what my father told me, who had heard it from his father,” noted De Mahieu. Berger recruited the then-major Marcial Samaniego, who immediately became interested in the oral traditions.

Supposed entrance of the mound discovered in one of the hills

Samaniego was the head of the border detachment in those days. As an ethnography enthusiast, he was “very interested” in the supposed marks of Nordic origin that the German described to him. Thus, Berger, in 1941, “obtained from the Army the creation of the Geological and Archaeological Group (AGA), which hired him and where he worked hard and effectively.”

The engineer and Samaniego toured the region and found “inscriptions and drawings” on the rocks “that could not be attributed to the Indians” and other “numerous vestiges of a disappeared civilization.”

“Their sappers (from the Army, under the command of Samaniego) almost completely dismantled a hill on whose top was an imposing wall. No one, however, in Paraguay gave greater importance to the results obtained,” wrote De Mahieu.

The AGA ended up dissolved in 1945 and Fritz Berger, “discouraged and ill,” stayed in Amambay until the civil war of 1947, when he left Paraguay to die the following year in Dourados, Brazil.

According to De Mahieu, Berger did not stop talking about the “treasure of the White King” of Amambay until the end of his days, not without suspecting that “the Jesuits had already found it before.”

For his part, Samaniego used Berger's work to continue exploring, information that he later shared with Jacques de Mahieu.

FIRST EXPEDITION

At the beginning of 1975, De Mahieu had contacted “former Major Samaniego, already then Major General and Minister of National Defense of Paraguay,” who “did not hesitate to join the project.”

Samaniego received the delegation led by the Frenchman in his office and “deigned, in the course of a long audience, to give us indications as precise as they were prudent about the archaeological sites discovered 30 or so years earlier, and insisted on the role played , at that time, by Fritz Berger.”

De Mahieu assured the minister's support with a first collection of data, carried out two years earlier, in 1973, by his collaborators who "found on Guazú Hill a runic set of 61 characters already translated."

Samaniego revealed to De Mahieu the stories he kept from Berger and considered from the first moment that “Ipir was not a Guaraní name,” as he made an effort to link it with Futhark, the Norse language.

De Mahieu explains that the first expedition had as its main objective “to study the area and the accesses” and to understand “the purpose of the next stipulated expedition.” The team entered Cerro Corá led by Lieutenant Colonel Escobar, who already knew in advance the work carried out by the extinct AGA, 30 years before, and by the “almost blind Sergeant López.”

"Thanks to them we were able to locate the wall hill and the Aquidabán-Nigui wall, which was inside the National Park."

SECOND EXPEDITION

The second incursion to Cerro Corá took place between June and July 1976. On this occasion, the team was nourished by the participation of Professor Herman Munk, “runologist at the Institute of Human Sciences”, which De Mahieu directed in Buenos Aires. They were also joined by engineer Hansgeorg Bottcher, from the same university.

The group identified an alleged “wall” on one of the hills, because it had “a natural base,” but its slopes had “diverse characteristics that allow it to be differentiated into three groups.” According to De Mahieu, a geologist “confirmed that a phenomenon of this kind can only be the work of nature if it is a hard rock subjected to the action of glaciers,” which fueled the flame of curiosity.

“No geological movement could have broken the rock with the rigor of a geometer, nor carved sharp edges, nor respected the alignment of the blocks it would have produced,” he concluded.

Once the “wall” was located, De Mahieu marked the area. He was convinced that this formation was part of the ancient fortress of “Ipir, the White King,” about which Fritz Berger spoke so much to Minister Samaniego.

Without more provisions but with the enthusiasm of the first indications, the second expedition was set up with the firm hope of returning and excavating the alleged archaeological site.

THIRD EXPEDITION

For the third expedition, De Mahieu invited Paraguayan professor Vicente Pistilli, mathematician and engineer and director of the Paraguayan Institute of Human Sciences, who was fascinated by shedding some light on the pre-Columbian history of Paraguay.

Together, and with the consent of their companions, they launched the following hypothesis: "The 'wall' was part of a fortified enclosure whose other three sides were built with stakes, a procedure that the Vikings were not unaware of."

The group continued the search throughout the hill in question, finding caverns, walls and galleries full of drawings and marks, which De Mahieu "unequivocally" interpreted as being of "Aryan authorship" due to supposed representations of the Norse god ( Odin) and an amalgamation of mythological characters.

The sappers of the Paraguayan Army sent by Minister Samaniego worked tirelessly, revealing “indications of a mound that contained a true underground palace” in Yvyty Perõ, another of the sites that aroused great curiosity in the mission, since it would be the tomb. of “Ipir, the White King,” as Berger described.

At the end of the season, the team noted “great discoveries” such as “a tunnel” at the base of the “Murallón hill”, the same one that Berger, more than 30 years earlier, had already said he had located and through which De Mahieu kept the sappers “working as long as possible.”

THE "TUPAO CUE" OF TACUATÍ

The expedition left the forest and finally arrived at the town of Tacuatí. There, after a series of moves, De Mahieu and Pistilli obtained authorization to excavate the base of the church, which would have been built on, or with, the stones and parts of a much older temple, of supposed Viking inspiration, to which the locals referred to it as the Tupao Cue.

“The foundations are made of carved stone and, well, the remains of thick wooden pillars, almost petrified, can be seen, some of which we took back to Buenos Aires to study. The blocks, fitted without mortar, are carved with a precision that involves the use of metal tools. Thus, alignments of thick boulders can be seen, one of which bore the sign that corresponds to the runic gebo (g). According to various testimonies, the base would have been larger if it had not been for the work of the locals, who over the years have removed the stones to build bread ovens.”

De Mahieu wrote that these indications would be difficult to refute, since “the Jesuits never settled in Tacuatí” and the remains of the Tupao Cue are not attributable to the natives, “who did not know how to work stone.”

“The wall we unearthed supported walls made of squared logs, in the Viking style, which explains the thick wooden pillars we excavated on the south side. “This is an indication of the Aryan origin of the Tupao Cue,” said De Mahieu.

De Mahieu closed his stay in Paraguay with a last visit to Minister Samaniego, with the corresponding report, and returned to Argentina along with his entire team. In the following years, he dedicated himself to classifying his discoveries, disseminating them through the Institute of Human Sciences of Buenos Aires. Some of the photographs that were taken during those days were included in the book “The Viking King of Paraguay (Hachette publishing house, 1979).

By Gonzalo Caceres

Source: La Nacion (Asuncion, Paraguay) November 5, 2023

The Viking saga inspired veritable rivers of ink. From Scandinavia to Byzantium, passing through the North Sea, the Mediterranean, the British Isles, Sicily; southern, central, eastern and western Europe and Kievan Rus, among many other locations, that intrepid people of warriors and merchants took to the sea with such determination that they expanded their influence with the help of their fast longships.

But not everything was blood, fire and conquest; also discovery and colonization. The oldest records speak of names that reached the most remote points of the world known until then and to lands never seen before.

Jacques de Mahieu, in the Tacuatí excavations

Thanks to the site of L'Anse aux Meadows, on the island of Newfoundland, (Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador), it is known that the Vikings arrived in America at least 500 years before Christopher Columbus and it is speculated that this would be Vinland (the land described in the fascinating sagas of Eric the Red and that of the Greenlanders).

It is impossible to know if these skilled navigators considered – or could – continue further south of the American continent, explore the coasts and look for a safe place to spend the winter, or perhaps settle, interact and mix with the local population.

In this sense, there are academics who venture to work on this last possibility and outline bold theories. One of these was the controversial Jacques de Mahieu, a staunch defender of the Viking presence in pre-Columbian America.

Alleged runic inscriptions found on Guazú Hill

JACQUES DE MAHIEU

Jacques de Mahieu was born at the end of October 1915 in Marseille, France. It is known that during his youth he was involved with extreme right-wing movements and acted as an informant for the Vichy regime. Additionally, he fought against the Soviets in the service of Nazi Germany in the 33rd Charlemagne Volunteer SS Grenadier Division in the Waffen-SS.

As an –alleged– collaborator with the Nazis during the occupation, De Mahieu knew the risks of remaining in France and fled to Argentina shortly after the defeat of the Axis powers in World War II. The Frenchman took root in South American soil. He gained prestige and made a place for himself in the circles of anthropological studies in Buenos Aires, climbing positions until he reached the great university halls, enjoying an important reputation as a graduate in philosophy and a doctor in political sciences and economic sciences.

Our protagonist wrote at least half a dozen books about the alleged Viking adventures from the frozen wastelands of the north of the continent to the current border between Brazil and Paraguay.

To understand De Mahieu and the reasons that encouraged him to risk his life in the hot Paraguayan jungle and confront the entire conventional community of scientists, one must first understand the belief he professed.

De Mahieu mixed aristocratic and nationalist ideas, and focused his anthropological and sociological studies on the importance of race in history and culture. He was influenced by scientific racism and conceived theories “reinforced” with esotericism by embracing what related to the “Aryan race”, the cornerstone of Nazi mythology.

Likewise, he followed the theory of “Nordicism”, which is related to that of the “Aryan race” because the Nazis considered that the “Nordic race” (Vikings and their relatives) was the most superior branch of the “Aryan race” ( Herrenvolk).

Convinced of the great adventures that only members of the “Aryan race” could undertake, he soaked up the ability of the Vikings to reach, explore and conquer distant lands and looked for any evidence in these parts that would serve to highlight the greatness of the Vikings. “Aryans”.

FRITZ BERGER

Little is known about the German engineer Fritz Berger. In his fifties, obese and addicted to whiskey, Berger toured South America without settling anywhere. He was in Asunción during the Chaco War and provided “very good and loyal services” to the Paraguayan Army in command of one of the workshops where weapons captured from the Bolivian Army were reconditioned. After the war, he undertook the search for oil fields in the state of Paraná, Brazil, without much success.

His exploration took him to the border with Paraguay, where he “made discoveries of another nature” such as being “the largest runic complex in the world,” or what he believed were Viking runes.

Berger spent time with the natives, the oldest inhabitants of the area, and became obsessed with the runes when he was seduced by the stories of unimaginable treasures and vestiges of a disappeared, forgotten people, among versions that he collected from his talks with the aboriginal elders. .

“At that time there reigned in the region a powerful and wise king named Ipir. He was white and had a long blonde beard. With men of his race and with native warriors who were loyal to him, they lived in a large village located on the top of a hill. He had fearsome weapons and great wealth in gold and silver. One day, however, he was attacked by wild tribes and disappeared forever. This is what my father told me, who had heard it from his father,” noted De Mahieu. Berger recruited the then-major Marcial Samaniego, who immediately became interested in the oral traditions.

Supposed entrance of the mound discovered in one of the hills

Samaniego was the head of the border detachment in those days. As an ethnography enthusiast, he was “very interested” in the supposed marks of Nordic origin that the German described to him. Thus, Berger, in 1941, “obtained from the Army the creation of the Geological and Archaeological Group (AGA), which hired him and where he worked hard and effectively.”

The engineer and Samaniego toured the region and found “inscriptions and drawings” on the rocks “that could not be attributed to the Indians” and other “numerous vestiges of a disappeared civilization.”

“Their sappers (from the Army, under the command of Samaniego) almost completely dismantled a hill on whose top was an imposing wall. No one, however, in Paraguay gave greater importance to the results obtained,” wrote De Mahieu.

The AGA ended up dissolved in 1945 and Fritz Berger, “discouraged and ill,” stayed in Amambay until the civil war of 1947, when he left Paraguay to die the following year in Dourados, Brazil.

According to De Mahieu, Berger did not stop talking about the “treasure of the White King” of Amambay until the end of his days, not without suspecting that “the Jesuits had already found it before.”

For his part, Samaniego used Berger's work to continue exploring, information that he later shared with Jacques de Mahieu.

FIRST EXPEDITION

At the beginning of 1975, De Mahieu had contacted “former Major Samaniego, already then Major General and Minister of National Defense of Paraguay,” who “did not hesitate to join the project.”

Samaniego received the delegation led by the Frenchman in his office and “deigned, in the course of a long audience, to give us indications as precise as they were prudent about the archaeological sites discovered 30 or so years earlier, and insisted on the role played , at that time, by Fritz Berger.”

De Mahieu assured the minister's support with a first collection of data, carried out two years earlier, in 1973, by his collaborators who "found on Guazú Hill a runic set of 61 characters already translated."

Samaniego revealed to De Mahieu the stories he kept from Berger and considered from the first moment that “Ipir was not a Guaraní name,” as he made an effort to link it with Futhark, the Norse language.

De Mahieu explains that the first expedition had as its main objective “to study the area and the accesses” and to understand “the purpose of the next stipulated expedition.” The team entered Cerro Corá led by Lieutenant Colonel Escobar, who already knew in advance the work carried out by the extinct AGA, 30 years before, and by the “almost blind Sergeant López.”

"Thanks to them we were able to locate the wall hill and the Aquidabán-Nigui wall, which was inside the National Park."

SECOND EXPEDITION

The second incursion to Cerro Corá took place between June and July 1976. On this occasion, the team was nourished by the participation of Professor Herman Munk, “runologist at the Institute of Human Sciences”, which De Mahieu directed in Buenos Aires. They were also joined by engineer Hansgeorg Bottcher, from the same university.

The group identified an alleged “wall” on one of the hills, because it had “a natural base,” but its slopes had “diverse characteristics that allow it to be differentiated into three groups.” According to De Mahieu, a geologist “confirmed that a phenomenon of this kind can only be the work of nature if it is a hard rock subjected to the action of glaciers,” which fueled the flame of curiosity.

“No geological movement could have broken the rock with the rigor of a geometer, nor carved sharp edges, nor respected the alignment of the blocks it would have produced,” he concluded.

Once the “wall” was located, De Mahieu marked the area. He was convinced that this formation was part of the ancient fortress of “Ipir, the White King,” about which Fritz Berger spoke so much to Minister Samaniego.

Without more provisions but with the enthusiasm of the first indications, the second expedition was set up with the firm hope of returning and excavating the alleged archaeological site.

THIRD EXPEDITION

For the third expedition, De Mahieu invited Paraguayan professor Vicente Pistilli, mathematician and engineer and director of the Paraguayan Institute of Human Sciences, who was fascinated by shedding some light on the pre-Columbian history of Paraguay.

Together, and with the consent of their companions, they launched the following hypothesis: "The 'wall' was part of a fortified enclosure whose other three sides were built with stakes, a procedure that the Vikings were not unaware of."

The group continued the search throughout the hill in question, finding caverns, walls and galleries full of drawings and marks, which De Mahieu "unequivocally" interpreted as being of "Aryan authorship" due to supposed representations of the Norse god ( Odin) and an amalgamation of mythological characters.

The sappers of the Paraguayan Army sent by Minister Samaniego worked tirelessly, revealing “indications of a mound that contained a true underground palace” in Yvyty Perõ, another of the sites that aroused great curiosity in the mission, since it would be the tomb. of “Ipir, the White King,” as Berger described.

At the end of the season, the team noted “great discoveries” such as “a tunnel” at the base of the “Murallón hill”, the same one that Berger, more than 30 years earlier, had already said he had located and through which De Mahieu kept the sappers “working as long as possible.”

THE "TUPAO CUE" OF TACUATÍ

The expedition left the forest and finally arrived at the town of Tacuatí. There, after a series of moves, De Mahieu and Pistilli obtained authorization to excavate the base of the church, which would have been built on, or with, the stones and parts of a much older temple, of supposed Viking inspiration, to which the locals referred to it as the Tupao Cue.

“The foundations are made of carved stone and, well, the remains of thick wooden pillars, almost petrified, can be seen, some of which we took back to Buenos Aires to study. The blocks, fitted without mortar, are carved with a precision that involves the use of metal tools. Thus, alignments of thick boulders can be seen, one of which bore the sign that corresponds to the runic gebo (g). According to various testimonies, the base would have been larger if it had not been for the work of the locals, who over the years have removed the stones to build bread ovens.”

De Mahieu wrote that these indications would be difficult to refute, since “the Jesuits never settled in Tacuatí” and the remains of the Tupao Cue are not attributable to the natives, “who did not know how to work stone.”

“The wall we unearthed supported walls made of squared logs, in the Viking style, which explains the thick wooden pillars we excavated on the south side. “This is an indication of the Aryan origin of the Tupao Cue,” said De Mahieu.

De Mahieu closed his stay in Paraguay with a last visit to Minister Samaniego, with the corresponding report, and returned to Argentina along with his entire team. In the following years, he dedicated himself to classifying his discoveries, disseminating them through the Institute of Human Sciences of Buenos Aires. Some of the photographs that were taken during those days were included in the book “The Viking King of Paraguay (Hachette publishing house, 1979).

By Gonzalo Caceres

Source: La Nacion (Asuncion, Paraguay) November 5, 2023