Discovery of ‘superhighways’ suggests early Mayan civilization was more advanced than previously thought

By Taylor Nicioli, CNN

With the thick vegetation of the northern Guatemala rainforests hiding its 2,000-year-old remnants, the full extent of the early Mayan way of life was once impossible to see. But laser technology has helped researchers discover a previously unknown 650-square-mile (1,683-square-kilometer) Maya site that offers startling new insights about ancient Mesoamericans and their civilization.

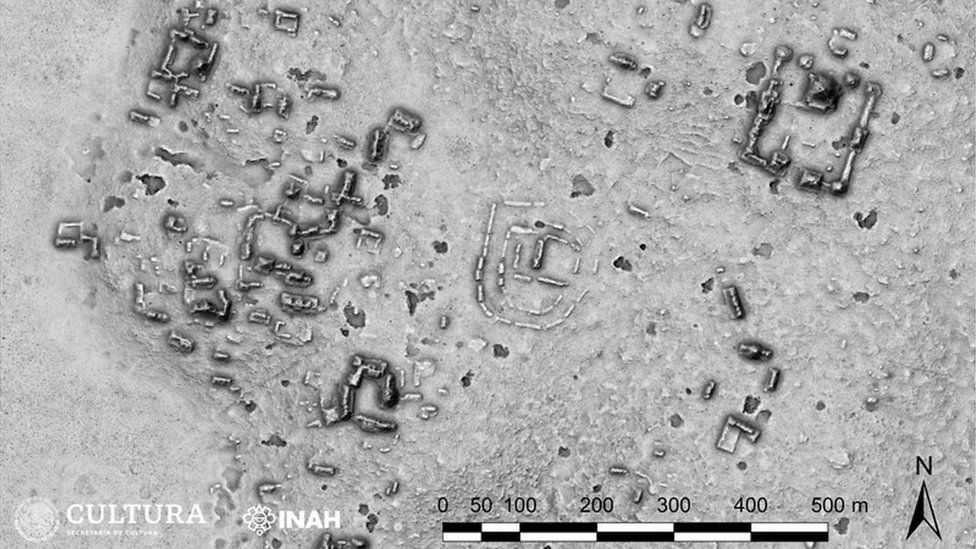

The researchers detected the vast site within the Mirador-Calakmul Karst Basin of northern Guatemala by using

LiDAR (light detection and ranging) technology, a laser mapping system that allows for structures to be detected below the thick tree canopies. The resulting map showed an area composed of 964 settlements broken down into 417 interconnected Mayan cities, towns and villages.

A 110-mile (177-kilometer) network of raised stone trails, or causeways, that linked the communities reveals that the early civilization was home to an even more complex society than previously thought, according to a recent analysis on the architecture groupings, published in the

journal Ancient Mesoamerica.

“They’re the world’s first superhighway system that we have,” said lead study author Richard Hansen, a professor of anthropology at Idaho State University. “What’s amazing about (the causeways) is that they unite all these cities together like a spiderweb … which forms one of the earliest and first state societies in the Western Hemisphere.”

The causeways, which rise above the seasonal swamps and dense forest flora of the Maya Lowlands, formed “a web of implied social, political, and economic interactions” with further implications regarding “strategies of governance” due to how difficult they would have been to build, according to the study.

‘Superhighways’ and society

The causeways were composed of a mixture of mud and quarry stone among several layers of limestone cement. Mayans likely made the elevated pathways with a process similar to the one they used to build their pyramids — by creating 10- to 15-foot (3- to 4.5-meter) stone boxes, then filling, stacking and leveling them off, according to Hansen. Several of these causeways were as wide as 131 feet (40 meters), nearly half the length of an American football field.

In Maya language, the word for causeway is “Sacebe” which translates to “white road.” On top of the raised roads was a thick layer of white plaster, which would have helped to increase visibility in the night as the plaster reflected moonlight, Hansen said.

“They didn’t have any pack animals in the Maya region … and we’re not thinking that they had wheeled vehicles on these causeways like Roman roads, like chariots or whatnot, but they were definitely built for people to interact, communicate and probably travel between sites,” said Marcello Canuto, anthropology professor and director of the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University.

Canuto, who was not involved in this study, was co-director on research that used the same LiDAR technology to reveal

over 60,000 ancient Mayan structures in 2018.

The causeways “were efforts that involve a lot of people, a lot of labor and coordination,” Canuto said. “They are complex work projects that would have required coordination and some form of hierarchy.”

Advanced laser mapping technology

LiDAR has been used to detect the remains of early Mayan civilizations since 2015, when two large-scale surveys were taken of the southern half of the Mirador-Calakmul Karst Basin. The technology allows for these discoveries to be made without harming the rainforests.

From an airplane flying overhead, light waves are pulsed down, and they bounce off objects below before returning to the sensor. Similar to sonar, which uses sound to locate structures, the LiDAR sensor tracks the amount of time each pulse takes to return and creates a three-dimensional map of the environment below.

“Imagine you’re in Poughkeepsie, New Jersey, and that’s all you can see, but you might catch this thing that we call the turnpike, right, but everything else is covered in jungle … you’ll have no idea that this turnpike might connect New York with Philadelphia,” Canuto said. “LiDAR is telling us everything that we found archaeologically over the last 100 years, here and there, is found everywhere … LIDAR lets us connect all the dots.”

Researchers are looking to gather more sampling and possibly locate more settlements through LiDAR technology this month to continue their research into the early Mayan civilization, according to Hansen.