You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Comfortably Numb

Antediluvian

- Joined

- Aug 7, 2018

- Messages

- 9,085

- Location

- Phone

(Also posted to the Edinburgh Fortean society thread).

Only noticed today, in local library

Borders Witch Hunt

A talk on the 17th century witchcraft trials in the Borders with Mary W. Craig, author and historian.

Friday 1st September

7:30 p.m.

Caddonfoot Hall, Clovenfords.

Public transport: I have checked thoroughly and without going into great detail, there is no guaranteed, late night public transport for a return to Edinburgh - there is a "20 minute walk" involved from Caddonfoot to nearest bus stop at the Clovvenfords hotel and even then, that requires making the bus traveling to Galashiels, to catch last train to Edinburgh.

If it's running and trust myself - not always the case.

And we all know what a "20 minute walk" means, when they neglect to mention "with suitable hiking equipment".

I hope to be there, tomorrow night and if anyone else likewise, please let me know - via a P.M., if preferable. Wish I had known about it sooner and not a late alert.

This is a must, for myself. Although living in the Borders, I only have a cursory knowledge of local witchcraft trials, a subject of interest, despite its macabre nature and zealous religious overtones.

Only noticed today, in local library

Borders Witch Hunt

A talk on the 17th century witchcraft trials in the Borders with Mary W. Craig, author and historian.

Friday 1st September

7:30 p.m.

Caddonfoot Hall, Clovenfords.

Public transport: I have checked thoroughly and without going into great detail, there is no guaranteed, late night public transport for a return to Edinburgh - there is a "20 minute walk" involved from Caddonfoot to nearest bus stop at the Clovvenfords hotel and even then, that requires making the bus traveling to Galashiels, to catch last train to Edinburgh.

If it's running and trust myself - not always the case.

And we all know what a "20 minute walk" means, when they neglect to mention "with suitable hiking equipment".

I hope to be there, tomorrow night and if anyone else likewise, please let me know - via a P.M., if preferable. Wish I had known about it sooner and not a late alert.

This is a must, for myself. Although living in the Borders, I only have a cursory knowledge of local witchcraft trials, a subject of interest, despite its macabre nature and zealous religious overtones.

ramonmercado

CyberPunk

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2003

- Messages

- 60,949

- Location

- Eblana

Not a very convincing witch.

A witch who practises “sex magic” to give herself and her partners “maximum pleasure” praises witchcraft for turning her life around after being “flat broke” in 2020, and now wants to “normalise” witchcraft in Ireland.

Billie Bryan (40) is the founder and president of a non-profit organisation and a cafe owner, originally from the Cayman Islands but now living in Galway with one of her partners, chef Jay Logan (21). She got into witchcraft in 2019 after becoming “captivated” by “stories of mysticism and the occult”.

Since then, Billie has given many tarot readings professionally. She claims she often gets messages from the Mother Goddess, a composite of various feminine deities from past and present world cultures and religions, and has recently had a “one-on-one conversation” with her.

Billie thanks manifestation and the Mother Goddess for her successes in life – in 2020, she was “in a bad place” but has since been able to move to Ireland and set up her own business.

https://www.breakingnews.ie/lifesty...craft-in-galway-with-themed-cafe-1525213.html

A witch who practises “sex magic” to give herself and her partners “maximum pleasure” praises witchcraft for turning her life around after being “flat broke” in 2020, and now wants to “normalise” witchcraft in Ireland.

Billie Bryan (40) is the founder and president of a non-profit organisation and a cafe owner, originally from the Cayman Islands but now living in Galway with one of her partners, chef Jay Logan (21). She got into witchcraft in 2019 after becoming “captivated” by “stories of mysticism and the occult”.

Since then, Billie has given many tarot readings professionally. She claims she often gets messages from the Mother Goddess, a composite of various feminine deities from past and present world cultures and religions, and has recently had a “one-on-one conversation” with her.

Billie thanks manifestation and the Mother Goddess for her successes in life – in 2020, she was “in a bad place” but has since been able to move to Ireland and set up her own business.

https://www.breakingnews.ie/lifesty...craft-in-galway-with-themed-cafe-1525213.html

Frideswide

Fortea Morgana :) PeteByrdie certificated Princess

- Joined

- Jul 14, 2014

- Messages

- 19,127

- Location

- An Eochair

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2019

- Messages

- 6,850

- Location

- Ontario, Canada

Hmmmm. Don't know if I believe her story of being flat broke. Quote from Wiki:Not a very convincing witch.

A witch who practises “sex magic” to give herself and her partners “maximum pleasure” praises witchcraft for turning her life around after being “flat broke” in 2020, and now wants to “normalise” witchcraft in Ireland.

Billie Bryan (40) is the founder and president of a non-profit organisation and a cafe owner, originally from the Cayman Islands but now living in Galway

https://www.breakingnews.ie/lifesty...craft-in-galway-with-themed-cafe-1525213.html

With a GDP per capita of $91,392, the Cayman Islands has the highest standard of living in the Caribbean, and one of the highest in the world.[9]

ramonmercado

CyberPunk

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2003

- Messages

- 60,949

- Location

- Eblana

Hmmmm. Don't know if I believe her story of being flat broke. Quote from Wiki:

With a GDP per capita of $91,392, the Cayman Islands has the highest standard of living in the Caribbean, and one of the highest in the world.[9]

The GDP is likely distorted though by resident tax exiles and financial services employees. At least she has a toyboy!

maximus otter

Recovering policeman

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2001

- Messages

- 15,761

Witchcraft claims linked to 17th century women’s jobs

Employment types open to 17th Century women came with a much higher risk of magical sabotage claims, a Cambridge University historian has found.

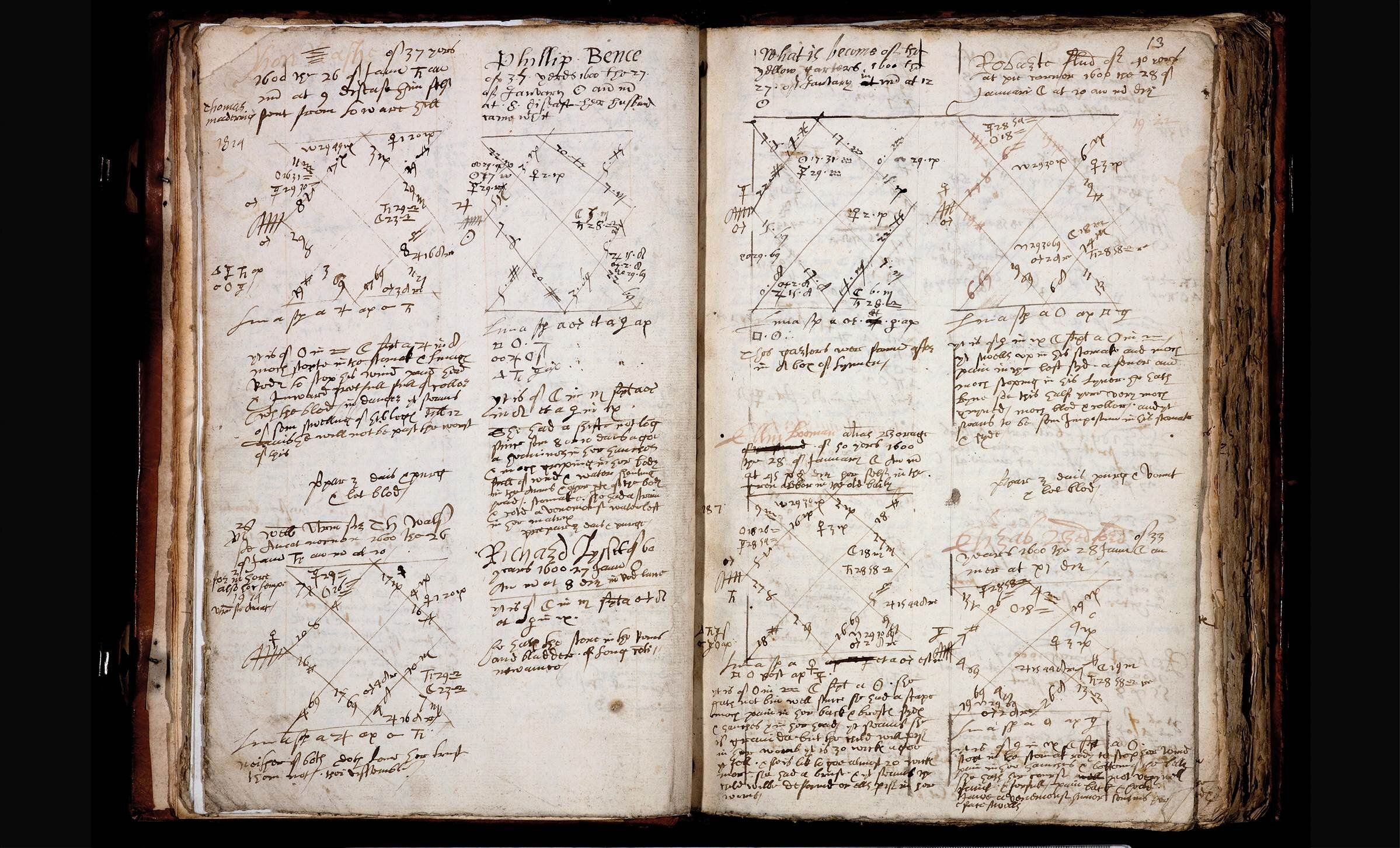

Dr Philippa Carter used the casebooks of a Buckinghamshire astrologer-doctor to analyse links between witchcraft accusations and women's occupations.

Richard Napier, whose casebooks are housed at Oxford University's Bodleian Library, was officially the rector of Great Linford, but gained a reputation as a "physician both of body and soul".

These [occupations] included healthcare, childcare, dairy production or livestock care.

In contrast to men's work, which often involved labour with sturdy or rot-resistant materials such as iron, fire or stone, women worked in areas where decay was more likely.

Dr Carter, from the department of history and philosophy of science, said: "Natural processes of decay were viewed as 'corruption'. Corrupt blood made wounds rankle and corrupt milk made foul cheese."

This meant they were much more likely to be linked to death, disease or spoilage, causing their clients suffering or financial loss.

Men were accused of witchcraft in the 16th and 17th Centuries, but figures suggest only 10 to 30% suspects were men.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-66854122

maximus otter

Employment types open to 17th Century women came with a much higher risk of magical sabotage claims, a Cambridge University historian has found.

Dr Philippa Carter used the casebooks of a Buckinghamshire astrologer-doctor to analyse links between witchcraft accusations and women's occupations.

Richard Napier, whose casebooks are housed at Oxford University's Bodleian Library, was officially the rector of Great Linford, but gained a reputation as a "physician both of body and soul".

These [occupations] included healthcare, childcare, dairy production or livestock care.

In contrast to men's work, which often involved labour with sturdy or rot-resistant materials such as iron, fire or stone, women worked in areas where decay was more likely.

Dr Carter, from the department of history and philosophy of science, said: "Natural processes of decay were viewed as 'corruption'. Corrupt blood made wounds rankle and corrupt milk made foul cheese."

This meant they were much more likely to be linked to death, disease or spoilage, causing their clients suffering or financial loss.

Men were accused of witchcraft in the 16th and 17th Centuries, but figures suggest only 10 to 30% suspects were men.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-66854122

maximus otter

maximus otter

Recovering policeman

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2001

- Messages

- 15,761

Witchcraft claims linked to 17th century women’s jobs

Employment types open to 17th Century women came with a much higher risk of magical sabotage claims, a Cambridge University historian has found.

Dr Philippa Carter used the casebooks of a Buckinghamshire astrologer-doctor to analyse links between witchcraft accusations and women's occupations.

Richard Napier, whose casebooks are housed at Oxford University's Bodleian Library, was officially the rector of Great Linford, but gained a reputation as a "physician both of body and soul".

These [occupations] included healthcare, childcare, dairy production or livestock care.

In contrast to men's work, which often involved labour with sturdy or rot-resistant materials such as iron, fire or stone, women worked in areas where decay was more likely.

Dr Carter, from the department of history and philosophy of science, said: "Natural processes of decay were viewed as 'corruption'. Corrupt blood made wounds rankle and corrupt milk made foul cheese."

This meant they were much more likely to be linked to death, disease or spoilage, causing their clients suffering or financial loss.

Men were accused of witchcraft in the 16th and 17th Centuries, but figures suggest only 10 to 30% suspects were men.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-66854122

maximus otter

l’ve just remembered that this is the same Richard Napier to whose notebook l referred here. It gives interesting details about the patients who approached him, their perceived problems and his diagnoses.

maximus otter

Ghost In The Machine

Justified & Ancient

- Joined

- Mar 17, 2014

- Messages

- 2,749

- Location

- Yorkshire

My dentist went to live and work there. And she was already loaded, by the look of her.Hmmmm. Don't know if I believe her story of being flat broke. Quote from Wiki:

With a GDP per capita of $91,392, the Cayman Islands has the highest standard of living in the Caribbean, and one of the highest in the world.[9]

maximus otter

Recovering policeman

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2001

- Messages

- 15,761

Practical Magic: The Lucrative Business of Being a Witch on Etsy and TikTok

When Maira Khan’s boyfriend left her last year, she was desperate to win him back. “I knew he was seeing someone else, but I didn’t know how serious it was,” said Ms. Khan, an influencer in Toronto. “I kind of just wanted her gone.”At a loss, she decided to consult the occult. “The first spell I bought was a cord cutting spell, which for me was about removing a third party,” Ms. Khan, 28, said. She found a witch through TikTok who only required the former couple’s name to perform a candle ritual: tying a length of twine around two candles and letting the wicks burn down until the string is broken by the flames. “She said that it went well,” Ms. Khan said.

It’s a good time to be a witch. Those steeped in the “craft” are part of a $2.3 billion industry in the larger psychic-services universe, a field that includes palm reading (palmistry), tarot cards (cartomancy) and astrology.

People aren’t dialing psychics from the phone book or knocking on witchy storefronts and back rooms for their fortune anymore — supernatural entrepreneurs have set up shop on TikTok and Etsy. There are nearly 36,000 Etsy sellers offering “psychic readings” and related paraphernalia like enchanted candles, apothecary kits, ritual oils and voodoo dolls.

https://dnyuz.com/2023/10/28/practi...business-of-being-a-witch-on-etsy-and-tiktok/

maximus otter

kamalktk

Antediluvian

- Joined

- Feb 5, 2011

- Messages

- 7,944

I tried getting a photo of her in a pose other than her looking down and angled at the camera, but it was impossible.have you tried floating her?

/witchcraft!

AmStramGram

Ephemeral Spectre

- Joined

- Mar 17, 2022

- Messages

- 295

(...)

Men were accused of witchcraft in the 16th and 17th Centuries, but figures suggest only 10 to 30% suspects were men.

(...)

I am currently reading a newly published book on the "Louis de Gaufridy" sorcery case in Southern France. A note in this book underlines the fact that in most parts of France, there were more documented cases of male witches than female witches. In the territory of the Parliament of Paris (the judiciary district covering roughly half of France, around the capital), more than 50% of condemned witches were male. In the Parliament of Rouen, the proportion of convicted males even reached 70%. This data contrasts heavily with the profile of British, German or Scandinavian witches, which were predominantly women. I wonder what were the figures in Italy and Spain, in the 16th and 17th century.

No explanation is given for these national contrasts. So we are left to wonder why in such and such country females were the usual suspects, while in other areas, suspicion predominantly fell on males.

Wasn't it a matter of religion ? In terms of number of convictions, it appears that the witch hunt was much fiercer in the Northern countries than in the South (contrary to what later Romanticists would claim). So protestantism might have played a role as a "reformist" religion aiming at the revival of a purer model of christianity. As in many "purification drives" along the world (in other religions), women might have been targeted because they were thought to be "temptresses" (as it is still the case in modern day countries where they are requested to cover their hair and stay at home - not doing so deserving them insults such as "you're immodest" or even beatings]).

"History is written by the victor", so I guess the way the history of the witch hunts was initially written may have put all the blame of the Catholic Holy Inquisition and presented protestantism a mild, beneficial evolution as opposed to the corruption of the Roman world. Yet, it suffices to compare a description of rural life in the Western Isles of Scotland before (see Martin Martin's accounts) and after the establishment of protestantism to measure the impact of the reformist faith on the development of extreme puritanism. In a couple of centuries, we pass from abundant festivals were the faithful drink and dance to their fill to a strict observance of the sabath ...

On the other hand, the Catholic world was split between ageless tradition and its own reformist drive aimed at facing the challenge of protestantism. So although there was also a hunt for "deviants", old practices were still aknowledged, especially the fact that medieval magic and conjuring was predominantly a clerical practice. Priests being males, when sorcery was to be considered, they remained a prime vehicle for witchcraft. Then it was up to who got the upper hand in the power struggles within the Church : traditionalists would just let "sorcerers" be (that's how the Frioulan "Benandanti" were handled by the Italian inquisition : none of them was executed ), while hardcore tridentine reformists would sue.

The Louis de Gaufridy's case rather supports this hypothesis as he was himself a priest. His case was judged by a militant reformist priest (Michaelis) while his bishop instead tried to protect him. So we can see the tension between diverging postures within the Catholic Church.

A second factor which might explain the North / South difference in scope and gender-focus may be "precedence". It may be that the first reported cases contributed to define what was then expected to be a witch in every country. And once the model was set, subsequent cases would be oriented towards this model.

In France, it appears that early documented witch trials focused on men. The Carroi de Marlou's trial, in the 1580s, is a prime example of this, four to five men (common folks) being convicted for only one old lady. Later on, the Gaudridy case focused on a priest seducing young girls in a monastic community. The case of Urbain Grandier at Loudun reproduces almost exactly the same model : again it is a priest leading young girls astray. And in the case of the possessions of Louviers, again a love affair between a priest and nuns is pivotal ... Thanks to the development of printing, these stories were largely broadcasted. That may have shaped peoples' attitudes towards what was to be expected of sorcery cases, which in turn tended to reinforce national trends in terms of gender positionning of witches / warlocks.

That's my hypothesis, but I might be deluded by the devil and the Pope !

*** edit : additional possible explanation ***

Ritual language might also have played its part : while the Catholics kept using Latin, in Protestant countries, the Bible was translated into the national language. Depending on the translation (translation is always a betrayal), it might have encouraged a harsher stance towards "magicians" ...

Last edited:

Steven

Something about catseye

- Joined

- Nov 5, 2023

- Messages

- 3,045

- Location

- UK

I was completely unaware of the late Mr Sharpe's work.

'In the mid-1990s the historian James Sharpe, who has died aged 77, wrote Instruments of Darkness, a book on witch-hunting in England that reopened a field of research that had been in the doldrums for a generation. Published in 1996, Jim’s book helped to make the study of British witchcraft what it is today: one of the most lively areas of historical writing.

Earlier historians had argued that whereas witch-hunting on the European continent was fantastical, dominated by beliefs about the devil, English witch-hunting was comparatively rational and down-to-earth, centred on beliefs about the practical harm that witches caused to people and animals. Jim showed that this was nonsense, and that English witch-hunting was also powered by fear of the devil and followed much the same pattern as many other European countries.'

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/15/james-sharpe-obituary

'In the mid-1990s the historian James Sharpe, who has died aged 77, wrote Instruments of Darkness, a book on witch-hunting in England that reopened a field of research that had been in the doldrums for a generation. Published in 1996, Jim’s book helped to make the study of British witchcraft what it is today: one of the most lively areas of historical writing.

Earlier historians had argued that whereas witch-hunting on the European continent was fantastical, dominated by beliefs about the devil, English witch-hunting was comparatively rational and down-to-earth, centred on beliefs about the practical harm that witches caused to people and animals. Jim showed that this was nonsense, and that English witch-hunting was also powered by fear of the devil and followed much the same pattern as many other European countries.'

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/15/james-sharpe-obituary

ramonmercado

CyberPunk

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2003

- Messages

- 60,949

- Location

- Eblana

Many Sámi burned at the stake during Norway's Witchcraft mania.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, there was a widespread witch hunt against people accused of witchcraft. In Norway, approximately 750 people were accused of witchcraft and around 300 of them sentenced to death, many of them burned at the stake, and many of them Sámi.

In Northern Norway and Finnmark, researchers have conducted an extensive study of these proceedings, including who was accused, what they were convicted of and what the punishment was. Their source material was court records.

Of 91 people sentenced to death in Finnmark during this period, 18 were Sámi.

Many questions still remain about what actually happened in Central Norway and in the South Sámi area, so historian Ellen Alm from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) has tried to gather as much information as possible. Through court records, she found that three Sámi people were accused of witchcraft: Finn-Kristin, Anne Aslaksdatter and Henrik Meråker, the latter of whom received a death sentence.

Since many Sámi people had Norwegian-sounding names, there may have been more.

Ph.D. Candidate and NTNU historian Anne-Sofie Schjøtner Skaar is now in the process of studying cases of witchcraft and magic that took place at Inderøy, Namdalen and Stjør- and Verdalen District Court in the 18th century.

By thoroughly reading and studying the court records from Nord-Trøndelag County, she has discovered new, interesting information.

She is investigating how the prosecution of witchcraft was gradually abolished during the 18th century.

"Hardly any research has been conducted into how the prosecution and phenomenon of witchcraft cases came to an end, so it is interesting to investigate. I am also studying whether Sámi people in the South Sámi areas were still being prosecuted in the 18th century," Schjøtner Skaar said. ...

https://phys.org/news/2024-04-witchcraft-trials-norway-18th-century.html

In the 16th and 17th centuries, there was a widespread witch hunt against people accused of witchcraft. In Norway, approximately 750 people were accused of witchcraft and around 300 of them sentenced to death, many of them burned at the stake, and many of them Sámi.

In Northern Norway and Finnmark, researchers have conducted an extensive study of these proceedings, including who was accused, what they were convicted of and what the punishment was. Their source material was court records.

Of 91 people sentenced to death in Finnmark during this period, 18 were Sámi.

Many questions still remain about what actually happened in Central Norway and in the South Sámi area, so historian Ellen Alm from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) has tried to gather as much information as possible. Through court records, she found that three Sámi people were accused of witchcraft: Finn-Kristin, Anne Aslaksdatter and Henrik Meråker, the latter of whom received a death sentence.

Since many Sámi people had Norwegian-sounding names, there may have been more.

Ph.D. Candidate and NTNU historian Anne-Sofie Schjøtner Skaar is now in the process of studying cases of witchcraft and magic that took place at Inderøy, Namdalen and Stjør- and Verdalen District Court in the 18th century.

By thoroughly reading and studying the court records from Nord-Trøndelag County, she has discovered new, interesting information.

She is investigating how the prosecution of witchcraft was gradually abolished during the 18th century.

"Hardly any research has been conducted into how the prosecution and phenomenon of witchcraft cases came to an end, so it is interesting to investigate. I am also studying whether Sámi people in the South Sámi areas were still being prosecuted in the 18th century," Schjøtner Skaar said. ...

https://phys.org/news/2024-04-witchcraft-trials-norway-18th-century.html

maximus otter

Recovering policeman

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2001

- Messages

- 15,761

A centuries-old Pendle Witches mystery could be over as archaeologists uncover 'best contender ever'

For something so synonymous with Pendle, so much of what led to the 1612 witch trials remains shrouded in mystery.

For years, doubts have been raised about precisely where the Pendle Witches are alleged to have cast their spells. But, perhaps, some of those questions could be at an end.

An archaeological dig at an alternate site has been hailed as "the best contender" yet.

The 17th century persecution of those suspected of being witches was sparked by the accession of James I who believed that witchcraft was a sin punishable by death. The group which became known as the Pendle Witches was made up of two families the Demdikes and and the Chattoxs.

In August 1612 Demdike's granddaughter Alizon Device was travelling to Trawden Forest in Pendle when she crossed paths with peddlar John Law. Alizon asked John for some metal pins, but he refused her request and walked away.

It was claimed that she had put a curse on him and he soon collapsed, and was paralysed and unable to speak. The community believed that Alizon had used withcraft to hurt John.

The matter was brought to the attention of local magistrate Roger Nowell and Alizon was soon arrested. Further arrests would follow after Alizon confessed and implicated neighbours and members of her own family.

Demdike had died in prison awaiting trial and after the 10 remaining 'witches' were convicted and hanged at Gallow's Hill, her home Malkin Tower, believed to be in the Forest of Pendle, was demolished. Extensive excavations have taken place to identify the location of Malkin Tower.

[An] episode of Digging up Britain's Past focused on [an area] which uncovered several features which archaeologists believe prove it to be the "best contender" for the true location of Malkin Tower.

Walls of the 17th century cottage at Lower Black Moss near Pendle Hill© Lorne Campbell/United Utilities/PA

Archaeologist Mike Woods said: "Malkin Tower Farm has had the name Malkyn attached to it since the 1500s and geophysical surveys carried out found two large rectangular anomalies that were found to be clay floored farm buildings dating to the early 17th century.

"With the name Malkin being the name for the site 100 years before the events surrounding the Pendle witchcraft trials and the discovery of the clay surfaced structures dated to the time of the witches, it is the best contender we have so far for the true location of Malkin Tower."

https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/ukne...er-best-contender-ever/ar-BB1meQ0I#fullscreen

maximus otter

Herr Cloaca

Abominable Snowman

- Joined

- Dec 26, 2020

- Messages

- 864

Dutch feminists campaign for national monument to ‘witches’

Three feminist campaigners in the Netherlands want to reclaim the insult “witch” and recognise the innocent victims of Dutch witch-hunts from the 15th to the 17th centuries with a national monument.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2...sts-campaign-for-national-monument-to-witches

So far, €35,000 has been raised in donations.

There's a list of accused witches in the Netherlands here - interestingly, the most recent being in 1823.

Three feminist campaigners in the Netherlands want to reclaim the insult “witch” and recognise the innocent victims of Dutch witch-hunts from the 15th to the 17th centuries with a national monument.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2...sts-campaign-for-national-monument-to-witches

So far, €35,000 has been raised in donations.

There's a list of accused witches in the Netherlands here - interestingly, the most recent being in 1823.

Last edited:

ramonmercado

CyberPunk

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2003

- Messages

- 60,949

- Location

- Eblana

Where won't you find Witches?

If asked, most people in the West would say that wicked witches who fly unaided or turn into animals don’t really exist. And, according to all available evidence, they would be right. It’s more difficult to prove that no one practises ‘witchcraft’, that is, conducts rites or utters curses in an attempt to harm others. Yet regardless of what people say about witches, or even what they believe, the idea of the witch is a universal constant looming over cultures from the islands of Indonesia to the pizza parlours of the modern United States.

Fifty years ago, as graduate students at Oxford, my wife and I were preparing to do anthropological fieldwork on the island of Sumba, in eastern Indonesia. Not long after beginning our research, an elderly ritual expert happened to mention that yet another ritualist – one of his rivals, as it later turned out – had ‘eaten’ a woman, the wife of a third man. This took me aback, in part because the woman in question was still alive. But I soon learned that the old man was accusing his rival of being a mamarung, a witch, who on Sumba is said to cause illness and death by invisibly eating people’s souls. Meeting secretly at night, Sumbanese witches also capture human souls, transform them into sacrificial animals, and then slaughter these to kill their victims and consume their bodies.

Thinking about this after returning to the United Kingdom, I realised that the same accusations of ritual killing and cannibalism were levelled during the ‘witch crazes’ of the early modern period, from the 14th to 17th centuries, in Europe, resulting in the persecution and killing of many of those accused. European witches were also said to feast on human flesh, transform themselves and others into animals, join nocturnal assemblies, and fly through the air. Far more recently, I was reminded of the universal idea of the ‘witch’ by Pizzagate – the QAnon conspiracy theory that Hillary Clinton and other members of a supposed global elite were killing and eating children in secret satanic rites, conducted while operating a paedophile ring in a pizza parlour in Washington, DC. As I read further, I realised that the Pizzagate accusations were recycled versions of allegations levelled during the 1980s and ’90s against owners and employees of US daycare centres who were identically accused of sacrificing children and eating them.

ut what is a ‘witch’? To prove that a belief in witches really is a human universal, we obviously need a definition. We also need to be clear about what ‘universal’ means. Actually, a definition commonly used by anthropologists, historians and other academics suits well enough. A witch is a human being who, motivated by malice, wilfully harms other people not openly by any physical methods, but by unseen, mystical means. Secret acts of ritual killing and cannibalism – essentially treating people like animals – are typical expressions of the witch’s hatred of humans. For example, witches among the Navaho of the America Southwest were accused of cannibalism, just like witches in New Guinea. Charged with the same horrendous acts, those US daycare workers would simply be seen as a variety of witches. In working through Satan, these rumoured devil-worshippers resemble not only the witches of medieval and early modern Europe, but equally witches described in Africa, Asia, the southwest Pacific, and native North and South America. For not only do non-Western witches kill people and eat them; they are similarly believed to obtain their powers through local demons. To cite one of many examples, Sumbanese witches possess evil spirits called wàndi that they keep inside their bodies and send out at night to attack their victims. ...

https://aeon.co/essays/the-universal-belief-in-witches-reveals-our-deepest-fears

Witches around the world

The belief in witches is an almost universal feature of human societies. What does it reveal about our deepest fears

If asked, most people in the West would say that wicked witches who fly unaided or turn into animals don’t really exist. And, according to all available evidence, they would be right. It’s more difficult to prove that no one practises ‘witchcraft’, that is, conducts rites or utters curses in an attempt to harm others. Yet regardless of what people say about witches, or even what they believe, the idea of the witch is a universal constant looming over cultures from the islands of Indonesia to the pizza parlours of the modern United States.

Fifty years ago, as graduate students at Oxford, my wife and I were preparing to do anthropological fieldwork on the island of Sumba, in eastern Indonesia. Not long after beginning our research, an elderly ritual expert happened to mention that yet another ritualist – one of his rivals, as it later turned out – had ‘eaten’ a woman, the wife of a third man. This took me aback, in part because the woman in question was still alive. But I soon learned that the old man was accusing his rival of being a mamarung, a witch, who on Sumba is said to cause illness and death by invisibly eating people’s souls. Meeting secretly at night, Sumbanese witches also capture human souls, transform them into sacrificial animals, and then slaughter these to kill their victims and consume their bodies.

Thinking about this after returning to the United Kingdom, I realised that the same accusations of ritual killing and cannibalism were levelled during the ‘witch crazes’ of the early modern period, from the 14th to 17th centuries, in Europe, resulting in the persecution and killing of many of those accused. European witches were also said to feast on human flesh, transform themselves and others into animals, join nocturnal assemblies, and fly through the air. Far more recently, I was reminded of the universal idea of the ‘witch’ by Pizzagate – the QAnon conspiracy theory that Hillary Clinton and other members of a supposed global elite were killing and eating children in secret satanic rites, conducted while operating a paedophile ring in a pizza parlour in Washington, DC. As I read further, I realised that the Pizzagate accusations were recycled versions of allegations levelled during the 1980s and ’90s against owners and employees of US daycare centres who were identically accused of sacrificing children and eating them.

ut what is a ‘witch’? To prove that a belief in witches really is a human universal, we obviously need a definition. We also need to be clear about what ‘universal’ means. Actually, a definition commonly used by anthropologists, historians and other academics suits well enough. A witch is a human being who, motivated by malice, wilfully harms other people not openly by any physical methods, but by unseen, mystical means. Secret acts of ritual killing and cannibalism – essentially treating people like animals – are typical expressions of the witch’s hatred of humans. For example, witches among the Navaho of the America Southwest were accused of cannibalism, just like witches in New Guinea. Charged with the same horrendous acts, those US daycare workers would simply be seen as a variety of witches. In working through Satan, these rumoured devil-worshippers resemble not only the witches of medieval and early modern Europe, but equally witches described in Africa, Asia, the southwest Pacific, and native North and South America. For not only do non-Western witches kill people and eat them; they are similarly believed to obtain their powers through local demons. To cite one of many examples, Sumbanese witches possess evil spirits called wàndi that they keep inside their bodies and send out at night to attack their victims. ...

https://aeon.co/essays/the-universal-belief-in-witches-reveals-our-deepest-fears

Swifty

doesn't negotiate with terriers

- Joined

- Sep 15, 2013

- Messages

- 35,086

‘Staggering array’ of witches’ marks discovered at English Heritage site

'As English Heritage welcomes thousands of visitors over the Halloween period, a new discovery has made Gainsborough Old Hall in Lincolnshire a clear contender for the spookiest site of them all.

The charity has uncovered a “staggering array” of witches’ marks and rare curses carved into the walls of the Tudor property, once visited by Henry VIII and his fifth Queen, Catherine Howard.'

https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/ukne...1&cvid=9a2a132dcec748a299b63978aa5305b2&ei=50

Herr Cloaca

Abominable Snowman

- Joined

- Dec 26, 2020

- Messages

- 864

England's last executed 'witch' may have survived

Prof Mark Stoyle, a historian at the University of Southampton, believes a spelling error by a court official meant the accused woman was not hanged, but instead lived for several years.

Alice Molland was sentenced at Exeter Castle, Devon, in 1685 for "bewitching" three of her neighbours.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4g2prk3v2eo

Prof Mark Stoyle, a historian at the University of Southampton, believes a spelling error by a court official meant the accused woman was not hanged, but instead lived for several years.

Alice Molland was sentenced at Exeter Castle, Devon, in 1685 for "bewitching" three of her neighbours.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4g2prk3v2eo

Herr Cloaca

Abominable Snowman

- Joined

- Dec 26, 2020

- Messages

- 864

Stormy Daniels is a witch

Daniels said that she has been a practicing witch since her childhood in New Orleans and that her 13-year-old daughter is also a practicing witch.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/oct/31/stormy-daniels-salem-witches

Daniels said that she has been a practicing witch since her childhood in New Orleans and that her 13-year-old daughter is also a practicing witch.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/oct/31/stormy-daniels-salem-witches

lordmongrove

Antediluvian

- Joined

- May 30, 2009

- Messages

- 5,796

The Occult : An Echo From Darkness (1970)

The clowns behind this are the same as the fools that fanned the flames of the Satanic Ritual Abuse debacle that destroyed so many families in the 80s and 90s. The guy with the silly tash doesn't even know that Lucifer and Satan are not the same thing or that the gods worshipped by other religions are not the same as the Christian boogeymen that they predate by thousands of years. The story of the human sacrifice is 100% bullshit created to prop up the narrative of this junk.maximus otter

Recovering policeman

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2001

- Messages

- 15,761

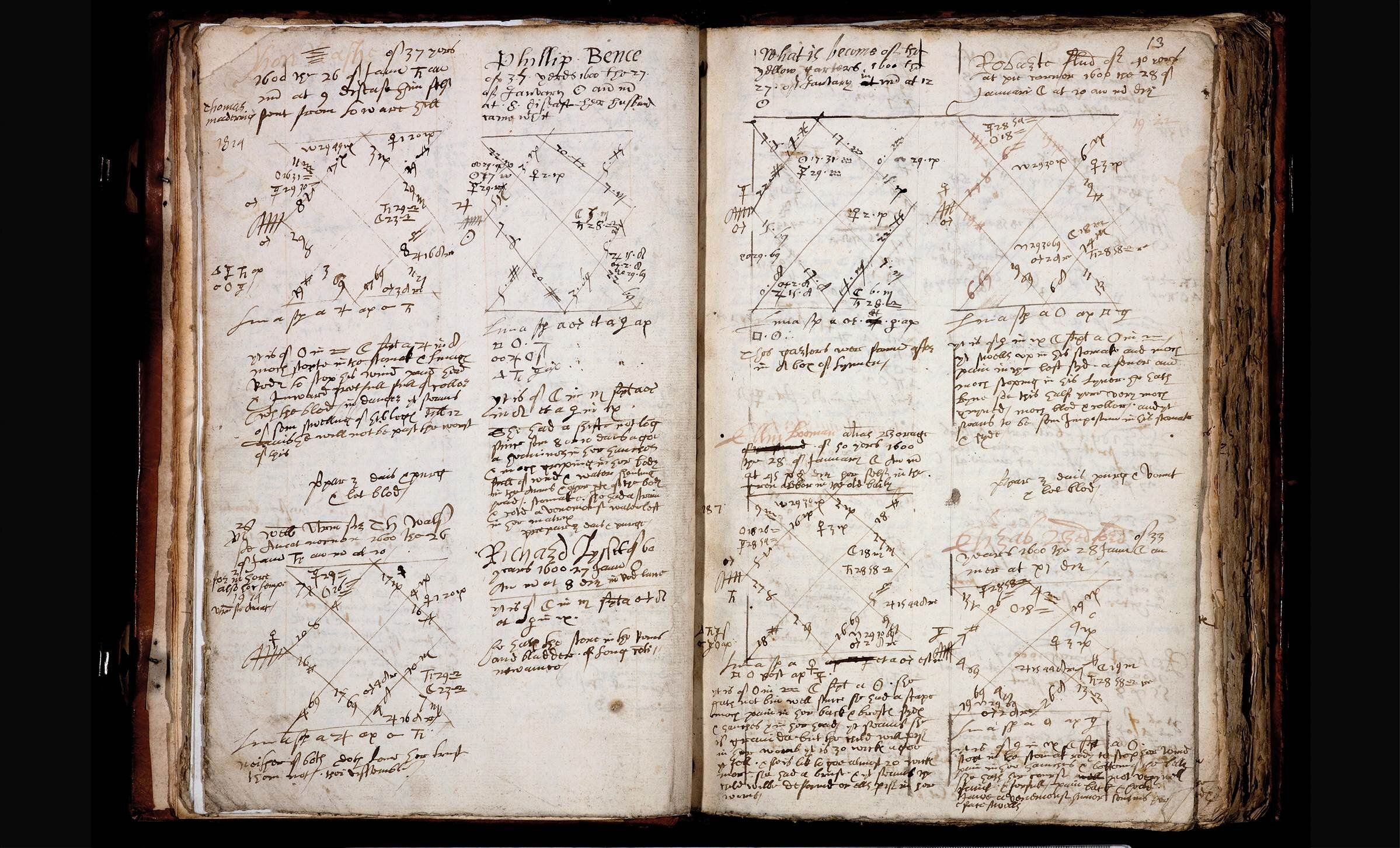

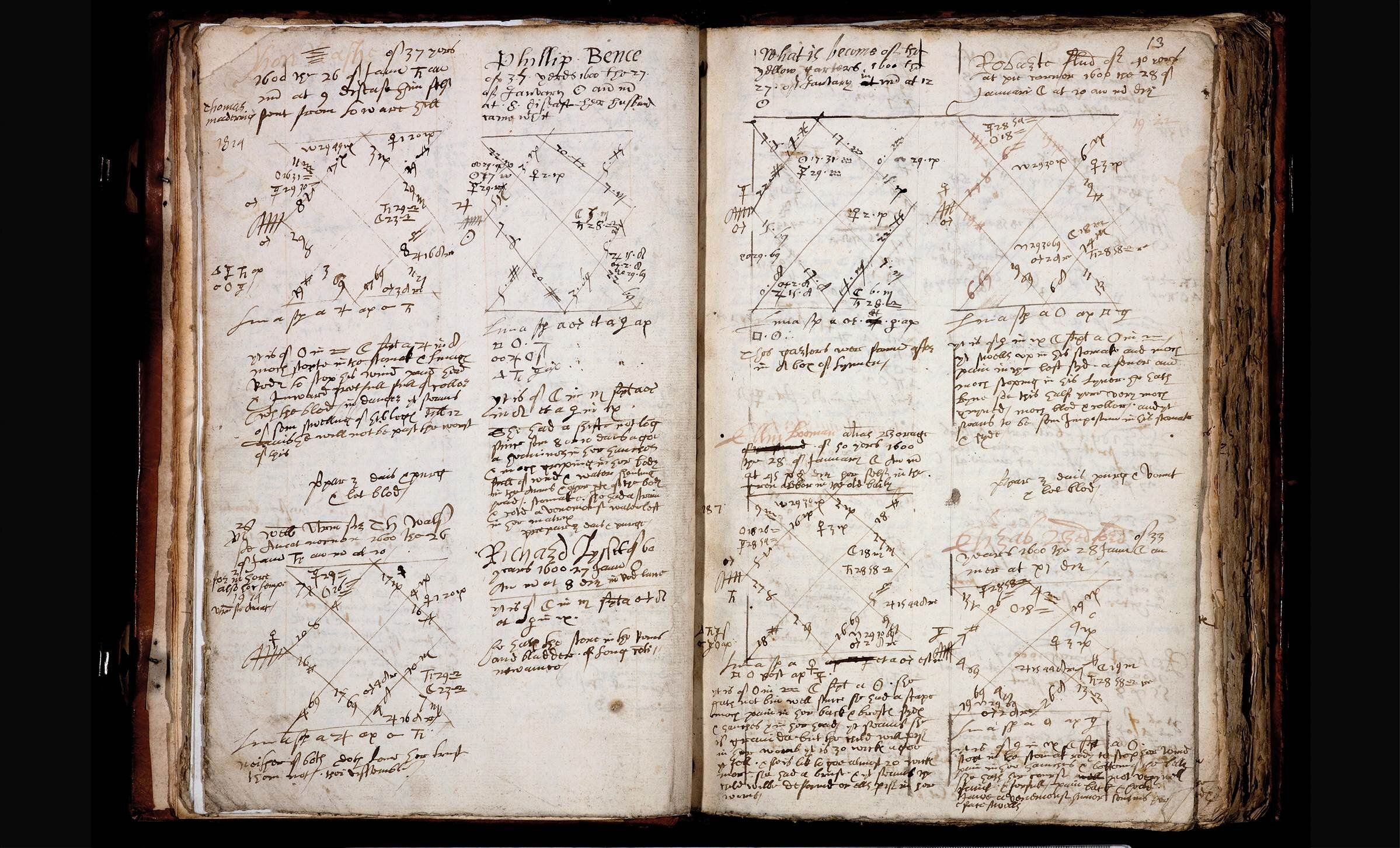

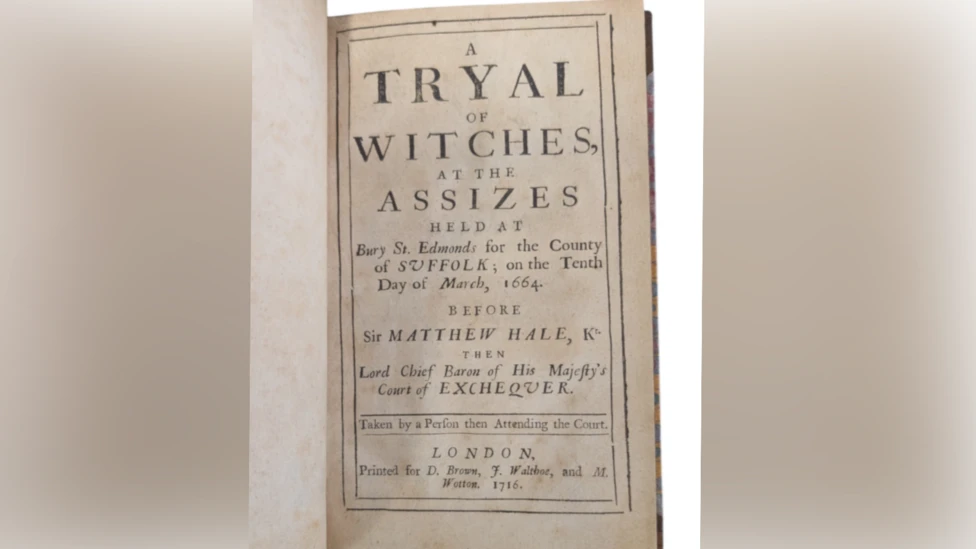

Historic book of town's witch trials to be displayed

A 300-year-old rare book that details events said to have inspired the infamous Salem Witch Trials will go on display.

The book, from 1716, was purchased by two charities for Moyse's Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, from a rare book seller.

It recounts the 1662 trial of Rose Cullender and Amy Denny, who were from Lowestoft and accused of being witches.

Not much was known of Cullender or Denny other than they were widows.

They were both accused of bewitching local children during various incidents and were tried at court in Bury St Edmunds.

Renowned judges including Sir Matthew Hale found them guilty and they were sentenced to death and later executed.

It will go on display as part of the Superstition: Strange Wonders and Curiosities exhibition at the museum, from 15 February to 6 April.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cvglz5qep98o

maximus otter

Last edited:

blessmycottonsocks

Beloved of Ra

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2014

- Messages

- 10,841

- Location

- Wessex and Mercia

The latest Dark Histories podcast is entitled "The Islandmagee Witchcraft Trials of 1711" and is well worth a listen.

As well as detailing the charges against the 8 women and one man in this infamous Irish witchcraft case, it describes testified accounts of what we would call today classic poltergeist activity. Stones and clods of earth being thrown, windows smashed and shutters banging, bedclothes being strewn around and a woman in bed levitating up to the canopy of her 4-poster bed. A thoroughly compelling piece of bed-time listening!

https://www.darkhistories.com/

As well as detailing the charges against the 8 women and one man in this infamous Irish witchcraft case, it describes testified accounts of what we would call today classic poltergeist activity. Stones and clods of earth being thrown, windows smashed and shutters banging, bedclothes being strewn around and a woman in bed levitating up to the canopy of her 4-poster bed. A thoroughly compelling piece of bed-time listening!

https://www.darkhistories.com/

Last edited:

maximus otter

Recovering policeman

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2001

- Messages

- 15,761

Scotland certifies official tartan to honor its 'witches'

There are thousands of officially registered Scottish tartan designs, but only one is dedicated to the “witches” of Scotland. Certified earlier this month, the tricolor pattern is intended as a memorial honoring the thousands of women who were falsely accused of witchcraft during the 16th through 18th centuries. Most of the victims were hanged following sham trials and unjust convictions. Following their executions, their bodies were also burned and denied proper burial.

Witches of Scotland co-founder Claire Mitchell thought of a…way to commemorate the Witchcraft Act’s many victims. In collaboration with designer Clare Campbell, Mitchell created a new tartan whose tricolor scheme, weaving, and patterns all directly recall the Scottish witchcraft trials.

Mitchell explained that the red threads represent the victims’ blood, the gray serves as a reminder of the ashes left after authorities burned their bodies, while the pink mimics the color of the tape used to tie legal documents. Each black square contains 173 threads for every year the Witchcraft Act was enforced, while the thin lines have either 15 or 17 threads—15 is the sum of the digits of the year the Witchcraft Act was passed (1+5+6+3), and 17 for when it was repealed (1+7+3+6).

https://www.popsci.com/science/scotland-witch-tartan/

maximus otter

There are thousands of officially registered Scottish tartan designs, but only one is dedicated to the “witches” of Scotland. Certified earlier this month, the tricolor pattern is intended as a memorial honoring the thousands of women who were falsely accused of witchcraft during the 16th through 18th centuries. Most of the victims were hanged following sham trials and unjust convictions. Following their executions, their bodies were also burned and denied proper burial.

Witches of Scotland co-founder Claire Mitchell thought of a…way to commemorate the Witchcraft Act’s many victims. In collaboration with designer Clare Campbell, Mitchell created a new tartan whose tricolor scheme, weaving, and patterns all directly recall the Scottish witchcraft trials.

Mitchell explained that the red threads represent the victims’ blood, the gray serves as a reminder of the ashes left after authorities burned their bodies, while the pink mimics the color of the tape used to tie legal documents. Each black square contains 173 threads for every year the Witchcraft Act was enforced, while the thin lines have either 15 or 17 threads—15 is the sum of the digits of the year the Witchcraft Act was passed (1+5+6+3), and 17 for when it was repealed (1+7+3+6).

https://www.popsci.com/science/scotland-witch-tartan/

maximus otter

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2019

- Messages

- 6,850

- Location

- Ontario, Canada

That's a nice looking tartan.Scotland certifies official tartan to honor its 'witches'

There are thousands of officially registered Scottish tartan designs, but only one is dedicated to the “witches” of Scotland. Certified earlier this month, the tricolor pattern is intended as a memorial honoring the thousands of women who were falsely accused of witchcraft during the 16th through 18th centuries. Most of the victims were hanged following sham trials and unjust convictions. Following their executions, their bodies were also burned and denied proper burial.

Witches of Scotland co-founder Claire Mitchell thought of a…way to commemorate the Witchcraft Act’s many victims. In collaboration with designer Clare Campbell, Mitchell created a new tartan whose tricolor scheme, weaving, and patterns all directly recall the Scottish witchcraft trials.

Mitchell explained that the red threads represent the victims’ blood, the gray serves as a reminder of the ashes left after authorities burned their bodies, while the pink mimics the color of the tape used to tie legal documents. Each black square contains 173 threads for every year the Witchcraft Act was enforced, while the thin lines have either 15 or 17 threads—15 is the sum of the digits of the year the Witchcraft Act was passed (1+5+6+3), and 17 for when it was repealed (1+7+3+6).

https://www.popsci.com/science/scotland-witch-tartan/

maximus otter