You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Joined

- Aug 7, 2001

- Messages

- 54,621

Death Star moon may be 'wonky or watery'

By Jonathan Webb, Science reporter, BBC News

The internal structure of one of Saturn's moons is either wonky or awash with water, according to a new study.

Mimas is nicknamed the Death Star because it resembles the infamous Star Wars space station.

It has a tell-tale wobble that is twice as big as expected for a moon with a regular, solid structure.

The researchers offer two explanations: either it has a vast ocean beneath its surface, or a rocky core with a weird shape resembling a rugby ball.

The study appears in Science Magazine.

Its authors are astronomers in the US, France and Belgium, who based their calculations on high-resolution photos of Mimas snapped by the Cassini spacecraft.

Cassini was sent to Saturn in 1997 to explore the planet and its many moons, which so far number 62 (53 with names).

The researchers built a detailed 3D model of Mimas using images taken from various angles, and tracked the movement of hundreds of reference points on its pockmarked surface.

"After carefully examining Mimas, we found it librates - that is, it subtly wobbles - around the moon's polar axis," said lead author Dr Radwan Tajeddine, who works at Cornell University in the US.

Apart from these gentle "librations", Mimas otherwise presents the same face to Saturn throughout its orbit.

Our own moon has a similar motion, with a small wobble that offers us slightly different views of the satellite over time.

But when Dr Tajeddine and his colleagues put all their measurements together, they found that the surface of Mimas swivels back and forth by 6km.

This is quite a wobble for a moon that measures less than 400km across. In fact, it is twice as much movement as expected, based on Mimas's size and its elliptical orbit.

"This is where we started thinking of more exotic interior models," Dr Tajeddine told BBC News.

First, the team tested whether the extra rotation could be explained by a deformity underneath the enormous Herschel Crater, one-third the size of Mimas itself, which gives the moon its signature appearance.

But even a "huge mass anomaly" created by the wallop that left the crater would not deliver the amount of movement that Dr Tajeddine's team had observed.

Instead, they wondered whether Mimas might be far from the simple, uniform sphere of ice and rock that most planetary scientists had previously assumed.

"Nature is essentially allowing us to do the same thing that a child does when she shakes a wrapped gift in hopes of figuring out what's hidden inside," Dr Tajeddine said.

His team settled on two likely plot twists, wrapped beneath Mimas's icy crust.

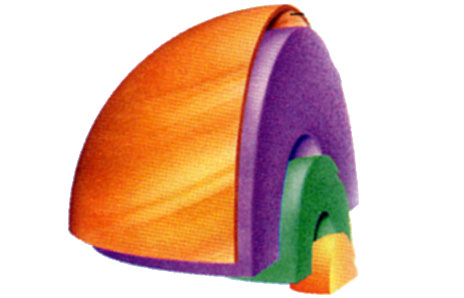

Firstly, their calculations suggested that the wobbles could arise from a core that was squashed or elongated by 20-60km: a huge, central rugby ball of rock.

Alternatively, the moon could have a normal spherical core and crust, but separated by a "global ocean". That way, Dr Tajeddine explained, "the shell can wobble more easily, because it's not attached to another mass".

Of the two explanations, he favours the subterranean sea.

"When we saw this wobbling, the first thing we thought of was an ocean," Dr Tajeddine said.

Either possibility would make Mimas a much more interesting research subject: "This brings the spotlight back to this moon, which was a little bit ignored."

Prof Chris Lintott, an astrophysicist at the University of Oxford, was surprised to hear of the new results.

"If you'd asked me before now, I would have said that Mimas is a boring, icy moon.

"If the ocean is really there, we're getting to the point where it's just completely standard for icy moons to have substantial bodies of water inside - and that could have interesting implications for how many of these things could support life." 8)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-29613671

By Jonathan Webb, Science reporter, BBC News

The internal structure of one of Saturn's moons is either wonky or awash with water, according to a new study.

Mimas is nicknamed the Death Star because it resembles the infamous Star Wars space station.

It has a tell-tale wobble that is twice as big as expected for a moon with a regular, solid structure.

The researchers offer two explanations: either it has a vast ocean beneath its surface, or a rocky core with a weird shape resembling a rugby ball.

The study appears in Science Magazine.

Its authors are astronomers in the US, France and Belgium, who based their calculations on high-resolution photos of Mimas snapped by the Cassini spacecraft.

Cassini was sent to Saturn in 1997 to explore the planet and its many moons, which so far number 62 (53 with names).

The researchers built a detailed 3D model of Mimas using images taken from various angles, and tracked the movement of hundreds of reference points on its pockmarked surface.

"After carefully examining Mimas, we found it librates - that is, it subtly wobbles - around the moon's polar axis," said lead author Dr Radwan Tajeddine, who works at Cornell University in the US.

Apart from these gentle "librations", Mimas otherwise presents the same face to Saturn throughout its orbit.

Our own moon has a similar motion, with a small wobble that offers us slightly different views of the satellite over time.

But when Dr Tajeddine and his colleagues put all their measurements together, they found that the surface of Mimas swivels back and forth by 6km.

This is quite a wobble for a moon that measures less than 400km across. In fact, it is twice as much movement as expected, based on Mimas's size and its elliptical orbit.

"This is where we started thinking of more exotic interior models," Dr Tajeddine told BBC News.

First, the team tested whether the extra rotation could be explained by a deformity underneath the enormous Herschel Crater, one-third the size of Mimas itself, which gives the moon its signature appearance.

But even a "huge mass anomaly" created by the wallop that left the crater would not deliver the amount of movement that Dr Tajeddine's team had observed.

Instead, they wondered whether Mimas might be far from the simple, uniform sphere of ice and rock that most planetary scientists had previously assumed.

"Nature is essentially allowing us to do the same thing that a child does when she shakes a wrapped gift in hopes of figuring out what's hidden inside," Dr Tajeddine said.

His team settled on two likely plot twists, wrapped beneath Mimas's icy crust.

Firstly, their calculations suggested that the wobbles could arise from a core that was squashed or elongated by 20-60km: a huge, central rugby ball of rock.

Alternatively, the moon could have a normal spherical core and crust, but separated by a "global ocean". That way, Dr Tajeddine explained, "the shell can wobble more easily, because it's not attached to another mass".

Of the two explanations, he favours the subterranean sea.

"When we saw this wobbling, the first thing we thought of was an ocean," Dr Tajeddine said.

Either possibility would make Mimas a much more interesting research subject: "This brings the spotlight back to this moon, which was a little bit ignored."

Prof Chris Lintott, an astrophysicist at the University of Oxford, was surprised to hear of the new results.

"If you'd asked me before now, I would have said that Mimas is a boring, icy moon.

"If the ocean is really there, we're getting to the point where it's just completely standard for icy moons to have substantial bodies of water inside - and that could have interesting implications for how many of these things could support life." 8)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-29613671

Mythopoeika

I am a meat popsicle

- Joined

- Sep 18, 2001

- Messages

- 53,369

- Location

- Inside a starship, watching puny humans from afar

That's no moon, that's...

OneWingedBird

Beloved of Ra

- Joined

- Aug 3, 2003

- Messages

- 15,417

I wonder what that does for the surface gravity?

Also reminds me loosely of the Unorthadox Engineers story with the planet where the gravity keeps changing direction, that turns out to be due to very dense 'moons' orbiting inside the planet.

Also reminds me loosely of the Unorthadox Engineers story with the planet where the gravity keeps changing direction, that turns out to be due to very dense 'moons' orbiting inside the planet.

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

GNC

King-Sized Canary

- Joined

- Aug 25, 2001

- Messages

- 33,481

Bruce Dern's been joyriding again?

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

NASA Saturn Mission Prepares for 'Ring-Grazing Orbits'

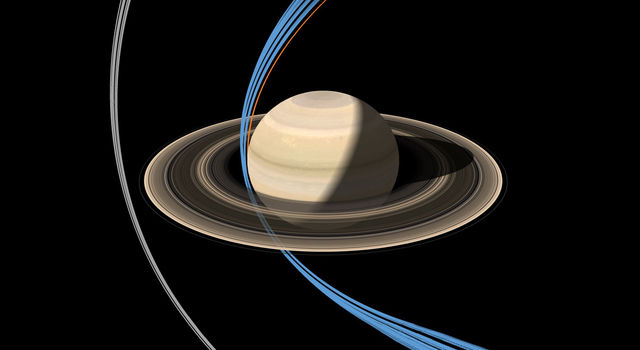

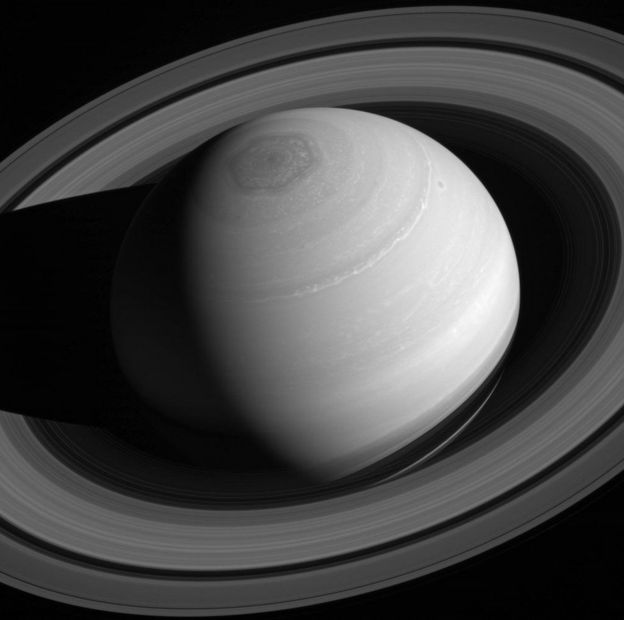

Cassini will soon begin a series of 20 orbits that fly high above and below Saturn's poles, plunging just past the outer edge of the main rings. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

› Full image and caption

First Phase in Dramatic Endgame for Long-Lived Cassini Spacecraft

A thrilling ride is about to begin for NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Engineers have been pumping up the spacecraft's orbit around Saturn this year to increase its tilt with respect to the planet's equator and rings. And on Nov. 30, following a gravitational nudge from Saturn's moon Titan, Cassini will enter the first phase of the mission's dramatic endgame.

› DOWNLOAD VIDEO Cassini's High-Flying, Ring-Grazing Orbits

Launched in 1997, Cassini has been touring the Saturn system since arriving there in 2004 for an up-close study of the planet, its rings and moons. During its journey, Cassini has made numerous dramatic discoveries, including a global ocean within Enceladus and liquid methane seas on Titan.

Between Nov. 30 and April 22, Cassini will circle high over and under the poles of Saturn, diving every seven days -- a total of 20 times -- through the unexplored region at the outer edge of the main rings.

"We're calling this phase of the mission Cassini's Ring-Grazing Orbits, because we'll be skimming past the outer edge of the rings," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. "In addition, we have two instruments that can sample particles and gases as we cross the ringplane, so in a sense Cassini is also 'grazing' on the rings."

On many of these passes, Cassini's instruments will attempt to directly sample ring particles and molecules of faint gases that are found close to the rings. During the first two orbits, the spacecraft will pass directly through an extremely faint ring produced by tiny meteors striking the two small moons Janus and Epimetheus. Ring crossings in March and April will send the spacecraft through the dusty outer reaches of the F ring.

"Even though we're flying closer to the F ring than we ever have, we'll still be more than 4,850 miles (7,800 kilometers) distant. There's very little concern over dust hazard at that range," said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at JPL.

The F ring marks the outer boundary of the main ring system; Saturn has several other, much fainter rings that lie farther from the planet. The F ring is complex and constantly changing: Cassini images have shown structures like bright streamers, wispy filaments and dark channels that appear and develop over mere hours. The ring is also quite narrow -- only about 500 miles (800 kilometers) wide. At its core is a denser region about 30 miles (50 kilometers) wide.

Saturn's rings were named alphabetically in the order they were discovered. The narrow F ring marks the outer boundary of the main ring system. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute › Larger image

So Many Sights to See

Cassini's ring-grazing orbits offer unprecedented opportunities to observe the menagerie of small moons that orbit in or near the edges of the rings, including best-ever looks at the moons Pandora, Atlas, Pan and Daphnis.

Grazing the edges of the rings also will provide some of the closest-ever studies of the outer portions of Saturn's main rings (the A, B and F rings). Some of Cassini's views will have a level of detail not seen since the spacecraft glided just above them during its arrival in 2004. The mission will begin imaging the rings in December along their entire width, resolving details smaller than 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) per pixel and building up Cassini's highest-quality complete scan of the rings' intricate structure.

The mission will continue investigating small-scale features in the A ring called "propellers," which reveal the presence of unseen moonlets. Because of their airplane propeller-like shapes, scientists have given some of the more persistent features informal names inspired by famous aviators, including "Earhart." Observing propellers at high resolution will likely reveal new details about their origin and structure.

And in March, while coasting through Saturn's shadow, Cassini will observe the rings backlit by the sun, in the hope of catching clouds of dust ejected by meteor impacts.

Preparing for the Finale

During these orbits, Cassini will pass as close as about 56,000 miles (90,000 kilometers) above Saturn's cloud tops. But even with all their exciting science, these orbits are merely a prelude to the planet-grazing passes that lie ahead. In April 2017, the spacecraft will begin its Grand Finale phase.

After nearly 20 years in space, the mission is drawing near its end because the spacecraft is running low on fuel. The Cassini team carefully designed the finale to conduct an extraordinary science investigation before sending the spacecraft into Saturn to protect its potentially habitable moons.

During its grand finale, Cassini will pass as close as 1,012 miles (1,628 kilometers) above the clouds as it dives repeatedly through the narrow gap between Saturn and its rings, before making its mission-ending plunge into the planet's atmosphere on Sept. 15. But before the spacecraft can leap over the rings to begin its finale, some preparatory work remains.

To begin with, Cassini is scheduled to perform a brief burn of its main engine during the first super-close approach to the rings on Dec. 4. This maneuver is important for fine-tuning the orbit and setting the correct course to enable the remainder of the mission.

"This will be the 183rd and last currently planned firing of our main engine. Although we could still decide to use the engine again, the plan is to complete the remaining maneuvers using thrusters," said Maize.

To further prepare, Cassini will observe Saturn's atmosphere during the ring-grazing phase of the mission to more precisely determine how far it extends above the planet. Scientists have observed Saturn's outermost atmosphere to expand and contract slightly with the seasons since Cassini's arrival. Given this variability, the forthcoming data will be important for helping mission engineers determine how close they can safely fly the spacecraft.

For details about Cassini's Ring-Grazing Orbits, including timing, closest approach distances and highlights, visit:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/2966/ring-grazing-orbits

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL designed, developed and assembled the Cassini orbiter

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6681

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

I hope NASA won't be providing pictures of that close encounterI accidentally grazed my ring last week, while drying myself after a shower - I dripped blood onto the bathroom mat!

OneWingedBird

Beloved of Ra

- Joined

- Aug 3, 2003

- Messages

- 15,417

I accidentally grazed my ring last week, while drying myself after a shower - I dripped blood onto the bathroom mat!

You'll be ok, just keep an eye on Uranus for a week or two.

- Joined

- Aug 7, 2001

- Messages

- 54,621

No, they didn't have a probe in the right position...I hope NASA won't be providing pictures of that close encounter

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

Cassini Makes First Ring-Grazing Plunge

This graphic shows the closest approaches of Cassini's final two orbital phases. Ring-grazing orbits are shown in gray (at left); Grand Finale orbits are shown in blue. The orange line shows the spacecraft's Sept. 2017 final plunge into Saturn. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

› Larger view

NASA's Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft has made its first close dive past the outer edges of Saturn's rings since beginning its penultimate mission phase on Nov. 30.

Cassini crossed through the plane of Saturn's rings on Dec. 4 at 5:09 a.m. PST (8:09 a.m. EST) at a distance of approximately 57,000 miles (91,000 kilometers) above Saturn's cloud tops. This is the approximate location of a faint, dusty ring produced by the planet's small moons Janus and Epimetheus, and just 6,800 miles (11,000 kilometers) from the center of Saturn's F ring.

About an hour prior to the ring-plane crossing, the spacecraft performed a short burn of its main engine that lasted about six seconds. About 30 minutes later, as it approached the ring plane, Cassini closed its canopy-like engine cover as a protective measure.

"With this small adjustment to the spacecraft's trajectory, we're in excellent shape to make the most of this new phase of the mission," said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California.

A few hours after the ring-plane crossing, Cassini began a complete scan across the rings with its radio science experiment to study their structure in great detail.

"It's taken years of planning, but now that we're finally here, the whole Cassini team is excited to begin studying the data that come from these ring-grazing orbits," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL. "This is a remarkable time in what's already been a thrilling journey."

Cassini's imaging cameras obtained views of Saturn about two days before crossing through the ring plane, but not near the time of closest approach. The focus of this first close pass was the engine maneuver and observations by Cassini's other science instruments. Future dives past the rings will feature some of the mission's best views of the outer regions of the rings and small, nearby moons.

Each of Cassini's orbits for the remainder of the mission will last one week. The next pass by the rings' outer edges is planned for Dec. 11. The ring-grazing orbits -- 20 in all -- will continue until April 22, when the last close flyby of Saturn's moon Titan will reshape Cassini's flight path. With that encounter, Cassini will leap over the rings, making the first of 22 plunges through the 1,500-mile-wide (2,400-kilometer) gap between Saturn and its innermost ring on April 26.

On Sept. 15, the mission will conclude with a final plunge into Saturn's atmosphere. During the plunge, Cassini will transmit data on the atmosphere's composition until its signal is lost.

Launched in 1997, Cassini has been touring the Saturn system since arriving there in 2004 for an up-close study of the planet, its rings and moons. During its journey, Cassini has made numerous dramatic discoveries, including a global ocean with indications of hydrothermal activity within the moon Enceladus, and liquid methane seas on another moon, Titan.

For details about Cassini's ring-grazing orbits, visit:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/2966/ring-grazing-orbits

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL designed, developed and assembled the Cassini orbiter.

More information about Cassini is at:

http://www.nasa.gov/cassini

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6690

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

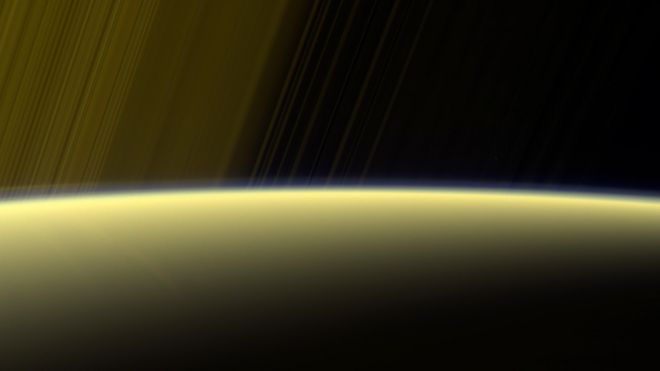

Cassini Beams Back First Images from New Orbit

[paste:font size="5"]

[/paste:font]

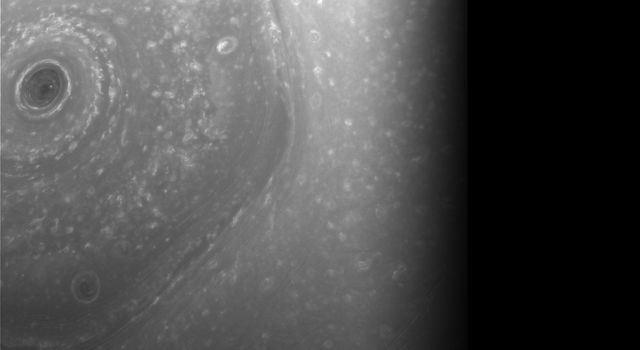

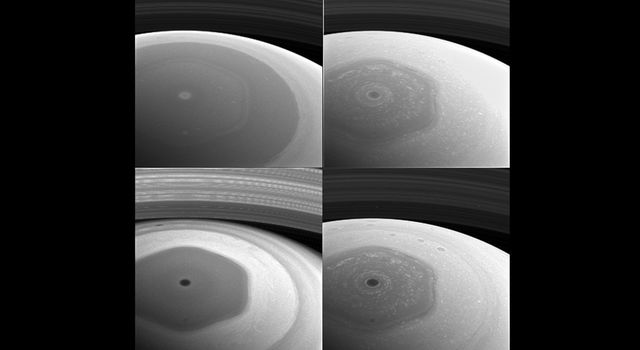

This view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft was obtained about half a day before its first close pass by the outer edges of Saturn's main rings during its penultimate mission phase. NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

› Full image and caption

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has sent to Earth its first views of Saturn's atmosphere since beginning the latest phase of its mission. The new images show scenes from high above Saturn's northern hemisphere, including the planet's intriguing hexagon-shaped jet stream.

Cassini began its new mission phase, called its Ring-Grazing Orbits, on Nov. 30. Each of these weeklong orbits -- 20 in all -- carries the spacecraft high above Saturn's northern hemisphere before sending it skimming past the outer edges of the planet's main rings.

Cassini's imaging cameras acquired these latest views on Dec. 2 and 3, about two days before the first ring-grazing approach to the planet. Future passes will include images from near closest approach, including some of the closest-ever views of the outer rings and small moons that orbit there.

"This is it, the beginning of the end of our historic exploration of Saturn. Let these images -- and those to come -- remind you that we've lived a bold and daring adventure around the solar system's most magnificent planet," said Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead at Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colorado.

The next pass by the rings' outer edges is planned for Dec. 11. The ring-grazing orbits will continue until April 22, when the last close flyby of Saturn's moon Titan will once again reshape Cassini's flight path. With that encounter, Cassini will begin its Grand Finale, leaping over the rings and making the first of 22 plunges through the 1,500-mile-wide (2,400-kilometer) gap between Saturn and its innermost ring on April 26.

On Sept. 15, the mission's planned conclusion will be a final dive into Saturn's atmosphere. During its plunge, Cassini will transmit data about the atmosphere's composition until its signal is lost.

Launched in 1997, Cassini has been touring the Saturn system since arriving in 2004 for an up-close study of the planet, its rings and moons. Cassini has made numerous dramatic discoveries, including a global ocean with indications of hydrothermal activity within the moon Enceladus, and liquid methane seas on another moon, Titan.

For details about Cassini's ring-grazing orbits, visit:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/2966/ring-grazing-orbits

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL designed, developed and assembled the Cassini orbiter.

More information about Cassini is at:

http://www.nasa.gov/cassini

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6693

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

The second set of 4 images is startling. The hexagonal storm is remarkable.

It's really bizarre.

skinny

Nigh

- Joined

- Mar 8, 2005

- Messages

- 9,200

I've just looked it up on the almighty Wikipedia and there's a bit of conjecture over what creates the effect. It is within the realms of explanation physics gives us but it seems so out of place there in the far reaches of the system.

What I know from that other bastion of pop culture, QI, is that the hex is probably the cosmos' most economical natural form, so apart from scale it is actually quite mundane. Witness the Giant's Causeway in Ireland as an example of the effect locally. The scale on Saturn's north pole makes it unique ... so far.

What I know from that other bastion of pop culture, QI, is that the hex is probably the cosmos' most economical natural form, so apart from scale it is actually quite mundane. Witness the Giant's Causeway in Ireland as an example of the effect locally. The scale on Saturn's north pole makes it unique ... so far.

Mythopoeika

I am a meat popsicle

- Joined

- Sep 18, 2001

- Messages

- 53,369

- Location

- Inside a starship, watching puny humans from afar

It's possibly due to a combination of things. The huge magnetic field and gravity field probably work together to produce constraints on a circle (a circle would normally be the natural shape).

It's possible also that far beneath the heavy atmosphere is a rocky body with a huge depression in it at the pole. It probably has a ragged edge, rapidly being worn down by the winds. If it eventually stops being hexagonal and goes back to circular, I'd say it was that.

It's possible also that far beneath the heavy atmosphere is a rocky body with a huge depression in it at the pole. It probably has a ragged edge, rapidly being worn down by the winds. If it eventually stops being hexagonal and goes back to circular, I'd say it was that.

eburacum

Papo-furado

- Joined

- Aug 26, 2005

- Messages

- 6,422

Interesting idea, but unlikely; the rocky core is buried deep beneath tens of thousands of kilometres of metallic and molecular hydrogen, and probably a layer of water ice - the fable of the Princess and the Pea springs to mind.It's possible also that far beneath the heavy atmosphere is a rocky body with a huge depression in it at the pole. It probably has a ragged edge, rapidly being worn down by the winds. If it eventually stops being hexagonal and goes back to circular, I'd say it was that.

OneWingedBird

Beloved of Ra

- Joined

- Aug 3, 2003

- Messages

- 15,417

Worth reading the whole thing about the plans for the end of Cassini - a number of higer risk orbits followed by being burned up in Saturn:

Bad Astronomy

The Cassini spacecraft has been orbiting Saturn since 2004, and is one of the most successful missions NASA has ever done. We’ve learned vast amounts of knowledge about the gigantic planet, its moons, and its rings.

But all good things … after more than a decade of Cassini sending back data and devastatingly beautiful images, NASA has decided to end the mission. With its final days approaching, NASA has decided to take more chances with it. The spacecraft has been sent into a series of risky trajectories, passing over Saturn’s north pole, then diving through the ring plane just outside the rings. These will be the closest approaches to the rings since Cassini first arrived at Saturn.

The new orbits started on Nov. 30, and a few days later Cassini passed over Saturn’s pole. The image above, taken on Dec. 3, shows amazing and lovely detail there. The dark oval is a storm over 2000 kilometers across—if it were placed over the U.S. it would stretch from California nearly to Missouri!

Bad Astronomy

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

Saturn's rings could contain millions of 'moonlets', new Nasa images reveal

Images from the Cassini spacecraft are most detailed ever taken, and include previously unseen features within the rings

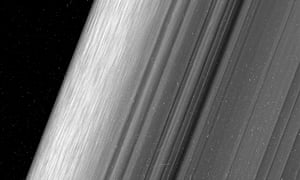

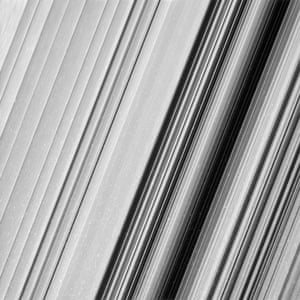

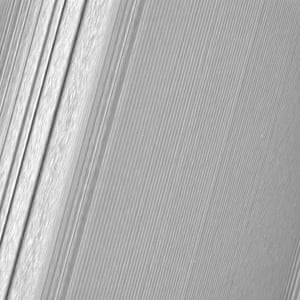

This image shows a region in Saturn’s outer B ring. Photograph: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Shares

- View more sharing options

210

Comments

239

Hannah Devlin Science correspondent

@hannahdev

Tuesday 31 January 2017 11.49 GMTLast modified on Tuesday 31 January 2017 15.37 GMT

Nasa has released spectacular images of Saturn’s rings, revealing that the rings may be home to millions of orbiting “moonlets”.

The images from the Cassini spacecraft resolve details on a scale of 550 metres – around the size of the tallest buildings on Earth. They include previously unseen features within the rings, including giant double-armed “propeller” structures that suggest a constellation of miniature moons are hidden within the planetary rings.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

A region in Saturn’s outer B ring. The many small, bright blemishes are created by cosmic rays and charged particle radiation near the planet. Photograph: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The rings comprise ice, dust and rocks, ranging in size from tiny specks to house-sized chunks. The so-called “propellers” are gaps in the material stretching thousands of miles across that scientists believe are created by moonlets.

The moonlets, sized somewhere between a house and 1km in diameter, clear the space immediately around them, but are not large enough to sweep clear their entire orbit around Saturn, as seen with the “shepherd” moons Pan and Daphnis.

The images also show grainy structure within individual rings, which astronomers refer to as “straw”, indicating where material has temporarily clumped together for reasons that astronomers are still trying to understand.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

This image features a density wave in Saturn’s A ring (at left). Density waves are accumulations of particles at certain distances from the planet. Photograph: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Carolyn Porco, the Cassini imaging lead based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said: “As the person who planned those initial orbit-insertion ring images, which remained our most detailed views of the rings for the past 13 years, I am taken aback by how vastly improved are the details in this new collection.”

Cassini, which has been studying Saturn’s rings from orbit for nearly 13 years, is now about halfway through its penultimate mission phase of 20 orbits that dive past the outer edge of the main ring system. These “ring-grazing” orbits will continue until late April and then Cassini will begin its grand finale, in which the craft will repeatedly plunge through the gap between the rings and Saturn. The first plunge is scheduled for 26 April.

https://www.theguardian.com/science...moonlets-new-nasa-images-reveal-cassini#img-1

OneWingedBird

Beloved of Ra

- Joined

- Aug 3, 2003

- Messages

- 15,417

This pic is bloody amazing - Cassini is near the end of it's life, so NASA are sending it on relatively risky orbits close in to Saturn and the ring system:

Bad Astronomy

What the what? We knew it was weirdly shaped from earlier images — maybe like a walnut or a flying saucer — but these new ones are still shocking. Look at it: It has a ridge along its equator that’s several kilometers high! Heck, it’s not a ridge, it’s a brim.

Except it’s not. It’s more like a sand dune. Made of ice. An ice dune. An ice dune that circles the moon.

OK, enough teasing, Here’s what’s what:

Pan is a wee little thing as moons go, only about 35 kilometers across its long axis. It actually is rather walnut shaped, and it orbits Saturn inside the A ring, the brightest of the planet’s main rings. There’s a gap in the ring, called the Encke Gap, and Pan orbits right in the center of the gap. That’s no coincidence: The gravity of the moon, though feeble, is enough to clear out ice particles in the ring, carving the 325-km-wide gap.

Bad Astronomy

eburacum

Papo-furado

- Joined

- Aug 26, 2005

- Messages

- 6,422

Looks like a hamburger, or a particularly generous cheese roll.

This is a big ridge of snow that goes all round Pan, made up of ring particles that have fallen on the equator of this moon.

There is a less-prominent, but still spectacular, ridge that goes all round Iapetus too.

This is a big ridge of snow that goes all round Pan, made up of ring particles that have fallen on the equator of this moon.

There is a less-prominent, but still spectacular, ridge that goes all round Iapetus too.

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

This pic is bloody amazing - Cassini is near the end of it's life, so NASA are sending it on relatively risky orbits close in to Saturn and the ring system:

Bad Astronomy

It looks like some giant alien child tried to make a model of Saturn out of Plasticine

Mythopoeika

I am a meat popsicle

- Joined

- Sep 18, 2001

- Messages

- 53,369

- Location

- Inside a starship, watching puny humans from afar

Looks artificial.

Mythopoeika

I am a meat popsicle

- Joined

- Sep 18, 2001

- Messages

- 53,369

- Location

- Inside a starship, watching puny humans from afar

Have they factored in the hard radiation that comes from Saturn?

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

Cassini probe heads towards Saturn 'grand finale'

By Jonathan AmosBBC Science Correspondent

- 28 minutes ago

Media captionEarl Maize: "We can't leave Cassini in an uncontrolled orbit near Saturn"

Cassini has used a gravitational slingshot around Saturn's moon Titan to put it on a path towards destruction.

Saturday's flyby swept the probe into an orbit that takes it in between the planet's rings and its atmosphere.

This gap-run gives the satellite the chance finally to work out the length of a day on Saturn, and to determine the age of its stunning rings.

But the manoeuvre means also that it cannot escape a fiery plunge into Saturn's clouds in September.

The US space agency (Nasa) is calling an end to 12 years of exploration and discovery at Saturn because the probe's propellant tanks are all but empty.

Controllers cannot risk an unresponsive satellite one day crashing into - and contaminating - the gas giant's potentially life-supporting moons, and so they have opted for a strategy that guarantees safe disposal.

"If Cassini runs out of fuel it would be uncontrolled and the possibility that it could crash-land on the moons of Titan and/or Enceladus are unacceptably high," said Dr Earl Maize, Nasa's Cassini programme manager.

"We could put it into a very long orbit far from Saturn but the science return from that would be nowhere near as good as what we're about to do," he told BBC News.

Image copyrightNASA/JPL

Image captionThe remainder of the mission will see Cassini repeatedly dive between the atmosphere and the rings

Cassini has routinely used the strong gravitational field of Titan to adjust its trajectory.

In the years that it has been studying the Saturnian system, the probe has flown by the haze-shrouded world on 126 occasions - each time getting a kick that bends it towards a new region of interest.

And on Saturday, Cassini pulled on the gravitational "elastic band" one last time, to shift from an orbit that grazes the outer edge of Saturn's main ring system to a flight path that skims the inner edge and puts it less than 3,000km above the planet's cloud tops.

The probe will make the first of these gap runs next Wednesday, repeating the dive every six and a half days through to its death plunge, scheduled to occur at about 10:45 GMT on 15 September.

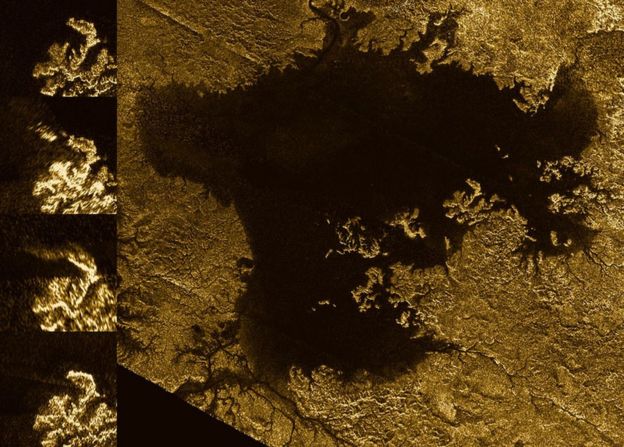

Image copyrightNASA/JPL-CALTECH/ASI/CORNELL

Image captionThe lakes and seas of Titan contain methane, ethane and other liquid hydrocarbons

Scientists used Saturday's pass of Titan to make some final close-up observations of the moon.

This extraordinary world is dominated at northern latitudes by great lakes and seas of liquid methane.

Cassini's radar was commanded once again to scan their depths and look for what have become known as "magic islands" - locations where nitrogen gas bubbles up from below to produce a transient bumpiness on the liquid surfaces.

This is a bitter-sweet moment for scientists. Titan has yielded so many discoveries, and although the probe will continue to encounter the moon in the coming months, it will never again get so close - less than 1,000km from ground level.

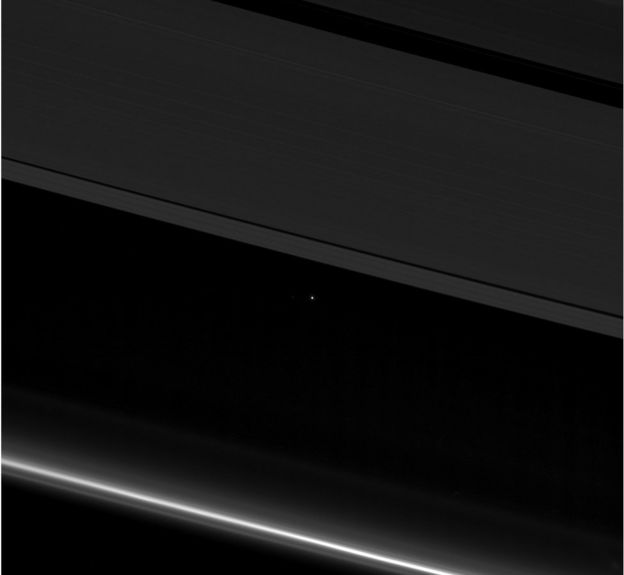

Image copyrightNASA/JPL

Image captionHome: Cassini has just taken this picture of Earth - a bright speck more than one billion km away

On the other hand, researchers have the prospect now of at last answering some thorny questions at Saturn itself.

These include the length of a day on the planet. Cassini so far has not been able to determine precisely the gas giant's internal rotation period.

From the close-in vantage afforded by the new orbit, this detail should become apparent.

"We sort of know; it's about 10.5 hours," said Prof Michele Dougherty, the Cassini magnetometer principal investigator from Imperial College, London, UK.

"Depending on whether you're looking in the northern hemisphere or the southern hemisphere - it changes. And depending on whether you're looking in the summer or winter seasons - it changes as well.

"So, there's clearly some atmospheric signal which we're measuring that's linked to weather and the seasons that's masking the interior of the planet," she told the BBC.

Image copyrightNASA/JPL

Image captionArtwork: Cassini will be destroyed when it plunges into the atmosphere of Saturn

The other major outstanding question is the age of Saturn's rings.

By getting inside them, Cassini will be able to weigh the great bands of ice particles.

"If the rings are a lot more massive than we expect, perhaps they're old - as old as Saturn itself; and they've been massive enough to survive the micrometeoroid bombardment and erosion and leave us with the rings we see today," conjectured Nasa project scientist Dr Linda Spilker.

"On the other hand, if the rings are less massive - they're very young, maybe forming as little as 100 million years ago.

"Maybe a comet or a moon got too close, got torn apart by Saturn's gravity and that's how we have the rings we see today."

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-39672263

Bigphoot2

Not sprouts! I hate sprouts.

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2005

- Messages

- 11,352

Cassini getting up close to Saturn

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-40902774

Cassini skims Saturn's atmosphere

By Jonathan AmosBBC Science Correspondent

Image copyrightNASA/JPL-CALTECH

Image captionCassini will "dip its toes" into the atmosphere during the final passes

The Cassini probe has begun the final phase of its mission to Saturn.

The satellite has executed the first of five ultra-close passes of the giant world, dipping down far enough to brush through the top of the atmosphere.

It promises unprecedented data on the chemical composition of Saturn.

It also sets the stage for the probe's dramatic end-manoeuvre next month when it will plunge to destruction in the planet's atmosphere.

Cassini is currently flying a series of loops around Saturn that thread the gap between its atmosphere and its rings.

Monday's swing-by saw the spacecraft go closer than ever before to the cloud tops - skimming just 1,600km (1,000 miles) above them, at 04:22 GMT (05:22 BST) on Monday.

This low pass was designed to allow the probe to directly sample the gases of the extended upper-atmosphere.

Etc

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-40902774

Ulalume

tart of darkness

- Joined

- Jan 3, 2009

- Messages

- 3,337

- Location

- Not Texas

Final pictures coming in from Cassini before it heads into Saturn's atmosphere.

Raw images here at NASA:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/galleries/raw-images?order=earth_date desc&per_page=50&page=0

Oh, and here's an end of mission timeline, if anyone wants to keep track -

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/grand-finale/cassini-end-of-mission-timeline/?linkId=42259312

Raw images here at NASA:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/galleries/raw-images?order=earth_date desc&per_page=50&page=0

Oh, and here's an end of mission timeline, if anyone wants to keep track -

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/grand-finale/cassini-end-of-mission-timeline/?linkId=42259312

Last edited:

skinny

Nigh

- Joined

- Mar 8, 2005

- Messages

- 9,200

Awesome. I still have my edition of Australian Sky and Space detailing the launch in the late 90s. What a voyage.

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/galleries/hall-of-fame/

The link above also has an area for the best pics from the mission. Amazing to see what was achieved. Incredible.

And an mp4 vid of the project's great successes here: https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/system/downloadable_items/851_JPL-20170404-CASSINf-0001-2560x1080.mp4

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/galleries/hall-of-fame/

The link above also has an area for the best pics from the mission. Amazing to see what was achieved. Incredible.

And an mp4 vid of the project's great successes here: https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/system/downloadable_items/851_JPL-20170404-CASSINf-0001-2560x1080.mp4