ramonmercado

CyberPunk

- Joined

- Aug 19, 2003

- Messages

- 60,949

- Location

- Eblana

What did the Romans ever do for us?

A team of anthropologists and behavioral specialists from several institutions in the U.S., working with a colleague from the U.K., has found that following the conquest of Great Britain in AD 43 by the Romans, the region experienced intensive economic growth.

In their study, published in the journal Science Advances, the group studied three types of archaeological evidence collected from multiple sites across the U.K. to measure economic growth.

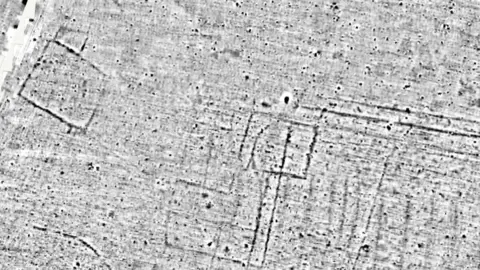

Over the past several decades, the U.K. has enacted laws requiring archaeological investigations on land under development. These studies have led to a large number of archaeological finds. For this new study, the researchers used data from such finds to measure the economic impact of Roman conquest and occupation over hundreds of years approximately 2,000 years ago.

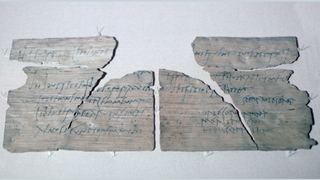

To gain insight into how Roman rule may have impacted Britain, the research team looked at three types of artifacts: buildings, coins and pottery. More specifically, they looked at how such artifacts changed in the years after the Roman conquest. Houses got bigger, they noted, and as people grew richer, they became more careless with their coins, resulting in more of them being lost between floorboard cracks.

As living standards improved, so did the quality and diversity of pottery used for preparing and eating meals. In making such comparisons, the research team was able to watch how economic growth impacted the people who had been conquered.

They found that in many cases, it had been what they describe as intensive—it greatly exceeded the type of growth that would have been expected for the region if the Romans had not arrived with their advanced technology and rules of business conduct.

The researchers suggest that improved roads and seaports made transport much easier, and business laws made work safer and improved efficiency. The Romans also introduced new technologies, such as advanced milling techniques, advanced concrete production and animal breeding programs that led to a greater variety of consumer products. The economic growth, they suggest, likely represented Great Britain catching up with the rest of the Roman empire. ...

https://phys.org/news/2024-07-archaeological-evidence-centuries-intensive-economic.html

A team of anthropologists and behavioral specialists from several institutions in the U.S., working with a colleague from the U.K., has found that following the conquest of Great Britain in AD 43 by the Romans, the region experienced intensive economic growth.

In their study, published in the journal Science Advances, the group studied three types of archaeological evidence collected from multiple sites across the U.K. to measure economic growth.

Over the past several decades, the U.K. has enacted laws requiring archaeological investigations on land under development. These studies have led to a large number of archaeological finds. For this new study, the researchers used data from such finds to measure the economic impact of Roman conquest and occupation over hundreds of years approximately 2,000 years ago.

To gain insight into how Roman rule may have impacted Britain, the research team looked at three types of artifacts: buildings, coins and pottery. More specifically, they looked at how such artifacts changed in the years after the Roman conquest. Houses got bigger, they noted, and as people grew richer, they became more careless with their coins, resulting in more of them being lost between floorboard cracks.

As living standards improved, so did the quality and diversity of pottery used for preparing and eating meals. In making such comparisons, the research team was able to watch how economic growth impacted the people who had been conquered.

They found that in many cases, it had been what they describe as intensive—it greatly exceeded the type of growth that would have been expected for the region if the Romans had not arrived with their advanced technology and rules of business conduct.

The researchers suggest that improved roads and seaports made transport much easier, and business laws made work safer and improved efficiency. The Romans also introduced new technologies, such as advanced milling techniques, advanced concrete production and animal breeding programs that led to a greater variety of consumer products. The economic growth, they suggest, likely represented Great Britain catching up with the rest of the Roman empire. ...

https://phys.org/news/2024-07-archaeological-evidence-centuries-intensive-economic.html